Cardowan

Before industry came to the region in the 1830s, the area of modern day Cardowan was taken up with the lands of the Cardowan Estate, owned by the Jeffray family.

The family included Dr James Jeffray, who was Professor of Anatomy at the University of Glasgow from 1790 until 1848. During his time as Professor, he became infamous for an experiment to test the effects of electricity - which was then a new science - on a dead body. In front of an audience, Dr Jeffray laid out the corpse of a recently executed murderer and connected it to a primitive type of battery. Much to Dr Jeffray’s (and the audience’s) horror, when the battery was switched on, the man’s body appeared to reanimate, with some witnesses claiming he leapt off the operating table.

Dramatic experiments aside, Dr Jeffray’s legacy was also cemented by being one of the founders of Glasgow Botanic Gardens, and for his support for the construction of the Glasgow to Garnkirk railway, the line of which ran through his estate at Cardowan and opened in 1831.

The opening of the railway - the first to link directly to the city of Glasgow - coincided with the opening of fireclay pits on Dr Jeffray’s land.

Ref: Map showing Cardowan House owned by Dr Jeffray, 1816.

Fireclay

Fireclay, a special type of hard-wearing clay, was mined from a seam that ran beneath the region around Cardowan and neighbouring communities. It was renowned for its properties of strength and heat-resistance. This made it an especially useful material as new industries were growing rapidly in central Scotland, with the strong bricks manufactured from fireclay used to build furnaces in the iron and steel works that were springing up across the area.

By the mid-19th century, the area around Cardowan, Glenboig and neighbouring communities was the largest manufacturer of fireclay products not just in Scotland, but the world. The bricks, pipes and other materials manufactured in the area’s fireclay works were not only used domestically but shipped around the world to feed growing industry elsewhere.

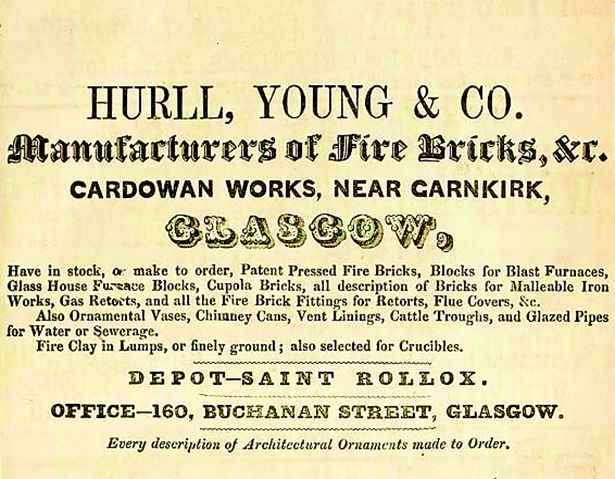

One of the most significant figures during the early years of fireclay manufacturing in Scotland was John Hurll. Hurll emigrated from Ireland to Scotland around 1835 and worked initially for the Garnkirk Coal Company. In the 1850s he joined forces with John Young to establish a fireclay works at Cardowan, on the north side of Garnkirk and Glasgow railway. The firm became known as Hurll, Young & Co and in 1862 it also took over Heathfield Works, east of Garnkirk. Later that decade Hurll and Young would go on to form the Glenboig Fire Clay Company to operate the Old Works at Glenboig.

The products made at the Cardowan works included firebricks, blast furnace blocks, gas fittings, ornamental vases, garden edgings, and chimney pots.

Ref: Newspaper advert for Hurll, Young & Co, 1861. Scottish Brick History.

https://www.scottishbrickhistory.co.uk/cardowan-fire-clay-works-stepps-north-lanarkshire/

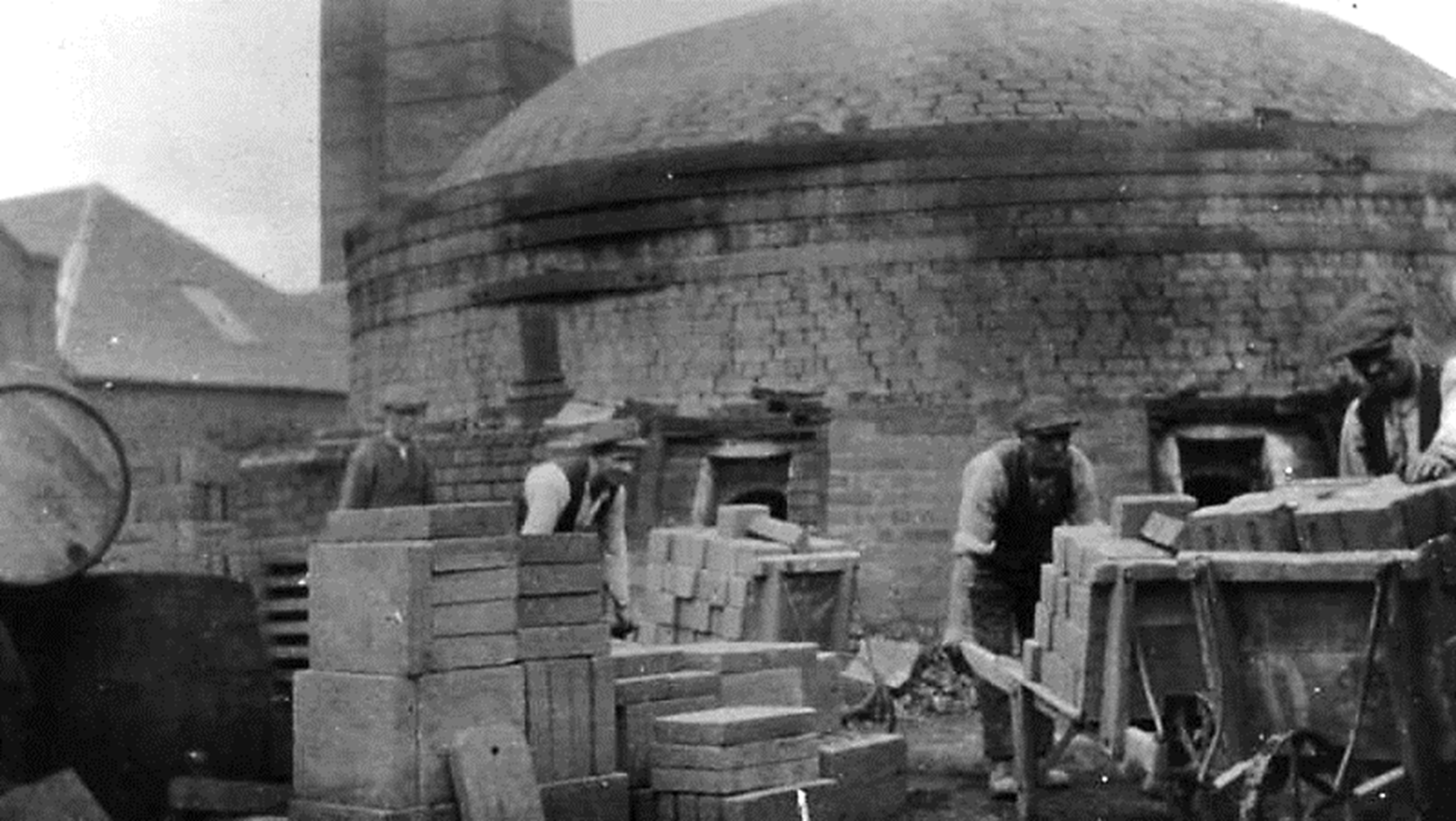

At this time, many of the products were made by hand, including thousands of individual firebricks created by skilled brickmakers. Brickmaking was back-breaking, repetitive and difficult work. Basic labourers worked a 57-hour week and were paid 18 or 19 shillings (around £50 in today’s money), whereas brickmakers - though only paid according to the number of bricks they produced - earned more.

Each brick was stamped with the name of the firm, but individual brickmakers had their own stamps which were unique to each man, with one letter perhaps being slightly larger than the others, or spaced slightly further apart. This meant brickmakers could identify their own bricks, but also served as a form of quality control, with poorer quality bricks being able to be traced back to the individual maker.

Ref: Brickmakers at Heathfield and Cardowan Fireclay Works. East Dunbartonshire Archive.

https://edlct.adlibhosting.com/Details/fullCatalogue/700002826

A noted brickmaker of the period was Thomas Coulter, who it is said made an average of 3,000 to 3,500 bricks during a 10-hour day but was known to make 4,000 bricks on a Friday, and 1,000 by 9am on a Saturday when he wanted to get away to play football!

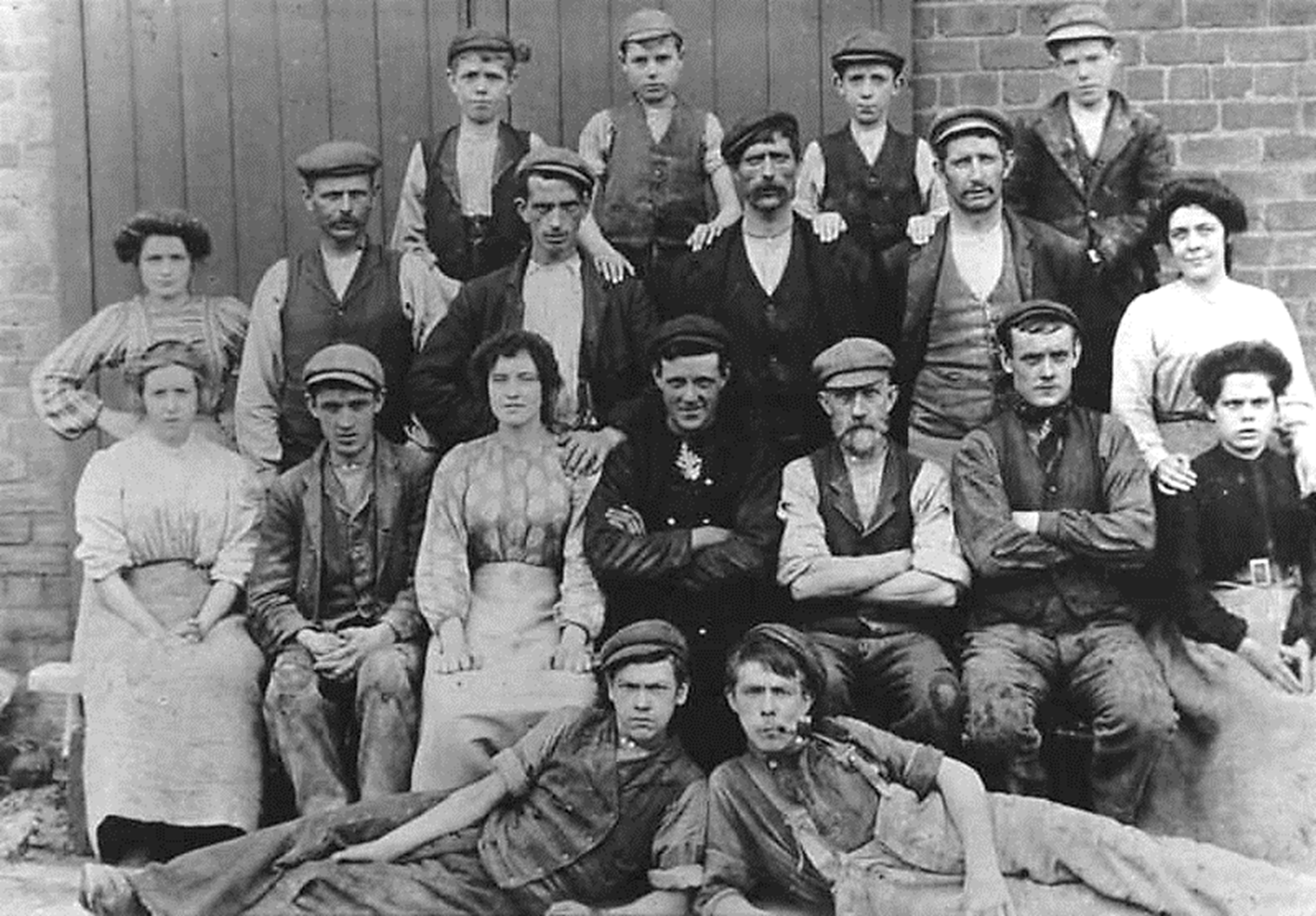

In the 1870s, Hurll and Young parted company, with John Hurll concentrating his efforts in Glenboig while John Young continued to manage the Cardowan and Heathfield works until it was sold to new owners in the 1880s. Such was the renown of the Cardowan brand that in the 1890s, John Young & Sons brought a legal case against the new owners for use of the Cardowan stamp, which they claimed they had no right to use as it had been recently copyrighted. The case was settled out of court.

Ref: Cardowan Works employees around 1900. East Dunbartonshire Archive.

https://edlct.adlibhosting.com/Details/fullCatalogue/700002871

The Cardowan Fireclay Works operated for around 50 years and continued to employ 40 to 50 men until it was forced to close in 1902, owing to what the newspapers at the time called a “dull trade”. While the nearby Heathfield works continued to operate until the late 1960s, Cardowan never reopened.

While it would be 20 years until the next major wave of industry came to Cardowan in the shape of the colliery, the fireclay works continued to have a lasting legacy across the globe. Bricks made at the site are still commonly unearthed as far afield as the USA, Canada and Australia.

Ref: Cardowan brick found in Massachusetts, USA. Scottish Brick History.

https://www.scottishbrickhistory.co.uk/cardowan-patent-brick-found-in-massachusetts-usa/

The Early Community

The opening of the fireclay works saw workers move to Cardowan and settle in the area, and what once had been a quiet, rural place became a growing village.

The large numbers of Irish workers moving to the area meant Cardowan had a mostly Catholic population. In the 1870s, there were around 1,000 Catholics living in the villages of Cardowan, Garnkirk, Heathfield, Moodiesburn, Hogganfield, Provanhall, and Queenslie, but the nearest church was in Coatbridge, four miles away.

The workers and their families wanted to build a church and school nearer to where they lived, so they petitioned the Archbishop of Glasgow, who agreed to their plans. As the majority of the area’s Catholic population were calculated to live within one and a half miles of Cardowan, it was chosen as the site for the new church, and St Joseph’s Roman Catholic Church was opened in 1875.

So, the church had been built, but the village still lacked a school, until it was agreed in 1880 that lessons could be held within the church. After morning mass, a curtain was drawn across the sanctuary and the building was transformed into a school. The average attendance in that first year was over a hundred pupils.

Even with limited materials and facilities, educational standards were good, with a government inspector’s report of 1889 noting that almost 92% of pupils from the Western District (including Cardowan) passed in reading, writing and arithmetic. Nevertheless, local parents were still keen on building a dedicated school, and their wishes were granted in 1901 when St Joseph’s Primary was opened next door to the church.

This school remained in operation until 1985 when the new St Joseph’s was built on the other side of Cardowan Road, opposite the church and original school, which is now used as a community space.

Ref: Original St Joseph’s Primary School, now a community space

Gartloch Distillery

With the community growing around the fireclay works, another industrial site was soon to open: Gartloch distillery. The distillery was built between 1898-1900 to the east of Cardowan, on the south side of the Garnkirk to Glasgow railway opposite the Garnkirk fireclay works.

Shortly after opening in 1900, its owners Northern Distilleries Ltd went bust. It is thought they had been hoping to profit from the 1890s whisky boom, but suffered from its collapse just as production at the distillery had started.

The distillery was sold to James Calder and Co, who operated it for 20 years until it was sold again, in 1921, to the Distiller’s Company Ltd, based in Edinburgh. Around this time, a legal case was brought against the distillery’s managers for allegedly hiring underage schoolgirls to work night shifts - we can only speculate that some of these girls may have been from nearby Cardowan, and perhaps attended St Joseph’s.

The distillery employed around 160 people in the 1920s, but by 1927 it had closed. It was perhaps the victim of the popular temperance movement, enacted into law in Scotland by the 1913 Temperance Act, which saw nearby Kirkintilloch and Kilsyth become two of Scotland’s first "dry" towns, and demand for alcohol dropping steeply, if not being eliminated entirely.

The buildings of Gartloch Distillery were mostly demolished in 1935, with only the warehouses and offices remaining until they too were torn down in the 1980s.

Ref: Photo from East Dunbartonshire Archives. Written on the back: “My mother, Margaret McPhail, with Gartloch Distillery in the background, taken c.1926.”

Cardowan Colliery

The 1920s saw the growth of another industry in Cardowan, one that was to outlast the short-lived distillery.

Cardowan Colliery had a series of coal pits sunk between 1924 and 1928, and was to eventually extract coal over an area of 4.5 square miles, making it one of the area’s largest collieries.

The colliery produced coal used in locomotives on the railways, as well as fuel for domestic fires. The pits had an initial workforce of around 800 men, making it a far larger employer than either the fireclay works or distillery had been.

By the 1930s, new houses were built for the growing workforce around the bottom end of Cardowan Road and Frankfield Road, to enable them to live closer and not have to travel to work.

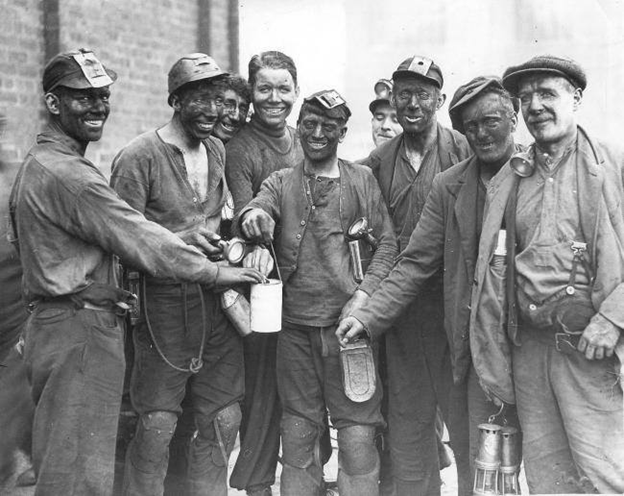

Ref: Cardowan miners in 1935, raising money to support radios for hospitals.

View on Facebook

Through the 1940s and 50s, the colliery continued to grow, employing at its peak 2,000 miners and producing 2,750 tonnes of coal every day, including coking coal which fuelled the ovens of Clyde Iron Works and the newly opened Ravenscraig steelworks. In 1957, the colliery was expanded, and a third mining shaft sunk to exploit new reserves.

By the late 60s, methane was being tapped from the pit to supply the newly-built Black & White whisky bottling plant in Stepps, but the colliery was by now reporting regular losses of £100,000 a month. A proposal was made to shut the mine, which would have resulted in the loss of 1,400 jobs. This was eventually overturned, and the colliery continued to be the main employer in Cardowan throughout the 1970s.

Ref: Winnie Ewing MP with Cardowan miners, date unknown.

View on Facebook

Locals who lived in Cardowan remember most young men finishing school at 16 and going straight to work in the pits. But mining was hard graft, often for little reward. Carol Quinn grew up in Cardowan in the 1970s and her dad worked in the pit. She remembers:

It was only at a young age I knew what poverty was, because I pallied with a girl that didn’t live in poverty. To me I used to say she was very rich, and posh, do you know what I mean? Because she had a quilt before I ever had a quilt, I still had an old patchy blanket. So, I knew back then what poverty was, yet my dad worked seven days a week as well. I remember my dad’s wage was £130 a week and that’s him working the seven days, and that still wasn’t covering the rent and everything else. Mick Walsh used to come here, he was a man, but you got tick [a loan] off him until the end of the week… and my mum was having to do that even although my dad was working, and I was very aware of it.

By the 1980s, the colliery was again threatened with closure as Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government continued its strategy to wind down heavy industry across the UK. The years preceding the national miners’ strike of 1984 were turbulent ones for the coal industry, and Cardowan was no exception. There was a tranche of redundancies in 1981, and significant pressure put on those who kept their jobs to transfer to other pits, including Polmaise near Stirling, or Longannet, Frances or Castlehill mines in Fife. Those who refused to transfer faced the threat of unemployment should Cardowan colliery be forced to close.

Some took up the offer, which included transfer fees of up to £750, resettlement payments and protected earnings in new jobs. However, miners at the other pits, notably Polmaise, recognised the tactics at play, and foresaw the consequences for Cardowan and the wider coal industry if they did not fight to protect local jobs. They refused entry to the Cardowan miners who showed up for work.

However, in the end, the government’s tactics worked. On Friday 26 August 1983, the National Coal Board announced Cardowan colliery was closing at 10pm that night.

Ref: The scene at Cardowan Colliery following the announcement it is to close.

https://shop.memorylane.co.uk/mirror/0500to0599-00534/anger-frustration-cardowan-colliery-bert-wheeler-21682125.html

Those who lost their jobs had few other local employment prospects, and many were forced to choose between travelling long distances to work at other mines, or face unemployment. Some were forced to pick up menial jobs to make ends meet, like collecting scrap metal or washing windows.

The closure of Cardowan brought to an end large scale deep mining in Lanarkshire, an industry which had once dominated the area and supported so many communities. Cardowan was one of six collieries to close around that time, in a wave of shutdowns that would foreshadow the coming miners’ strike.

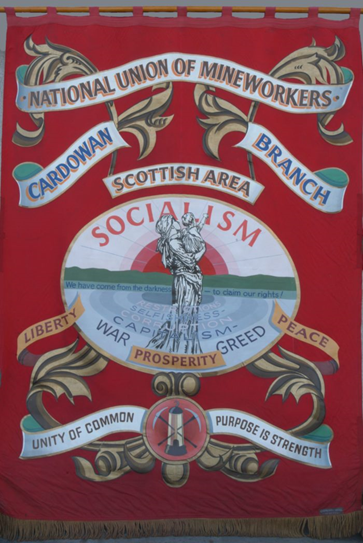

Ref: NUM banner, Cardowan Branch, date unknown.

This close-knit coal mining community stood in solidarity with their colleagues during the bitter battles of the strike, even though their own pit had already closed. Workers who remained at the Cardowan pit after it closed, to strip the mine, stood united with others in their industry. Women including Margaret Wegg, who had previously worked at the colliery canteen, organised a soup kitchen to feed workers who had been moved to other mines and were now on strike. They also made food parcels to deliver to miners’ families in the area.

Ref: Facebook: Cardowan Women’s Support Group protest during the miners’ strike, 1984.

Carol Quinn remembers it being a time of great tension and anxiety in the community:

And then the strike, when that hit, that was horrendous, absolutely horrendous because you were up at the picket line… And at that time when they were on strike the kids were getting fed, I don’t know if it was here or the hall at the time, but my mum wouldn’t allow us to go. We never once went down to it. It’s like the soup kitchen, it was called. But that’s the only major thing I can remember was the pit strike and it was horrendous. I mean I can remember… primary school, you used to be able to go up and go to the gates right at the back and you seen them all [the miners], going in and out. And that is where the picket line was, wasn’t it? And we were down a few times, but not a lot.

After dominating the community in Cardowan for so many years, the colliery, and the dangerous work performed by generations of Cardowan men, has left a legacy. Right from the outset, the pit was the scene of many fatal incidents. Three men were killed and eight injured during sinking of shafts in 1927, while in 1932, another 11 men were killed in an explosion. A fire at the colliery in 1960 injured 23 men, and an explosion in January 1982, in the dying days of the pit, injured another 40 more. As well as those who were injured and lost their lives, many more were left with debilitating health conditions as a result of their work.

Carol Quinn remembers the aftermath of the closure of the pit, and the effect it had on her family and the wider community:

Lost our community, totally lost our community. People moved away from here when it was here, because… when the pit shut, my dad had spoke to mum about moving to a different pit - my mum didn’t want to move, she didn’t want to move any of us... And when that happened it was just, it was… I mean my dad worked seven days a week and we couldn’t live... I think I spent most times outside because it was my mum and dad that were always arguing about money. I spent most of my childhood getting up in the morning and getting ready and just going out, I couldn’t wait to get out.

Sandra Mackie grew up in Cardowan and she also remembers the devastating effect the loss of the mine had:

My Granda was a blacksmith, he worked in the pit as a blacksmith as opposed to a miner. So, when the miners’ strike was happening, I was only young, so I didn’t understand what was happening. It wasn’t until I was an adult you can look back and think about the hardships that everybody went through because there wasn’t a family in Cardowan that didn’t have someone that had worked there. And then when the pit closed, I was still at school, Stepps Primary School. When obviously the pit had closed by that point and we got let out early so that we could go and watch the tower being demolished. So I was aware that there was sadness that that was happening and people in the community had been talking about it a lot, incessantly at the time, but as a child you didn’t… it was a spectacle as far as we were concerned because we got let out of school ten minutes early so that we could go and watch it being demolished. But obviously the adults in the community were not as excited about the effect it was having.

The legacy of the colliery continues to be acknowledged in Cardowan today. The roads on which new houses were built at the east of the village in the early 2000s were named after miners who lost their lives in the pit: Maroney Drive, McNab Crescent, McVey place, Watt Avenue, Reynolds Drive, Bradley Court, Flynn Gardens and Whiteford Road all honour miners killed in the 1932 explosion.

In October 2019, a memorial to those who were injured or killed at Cardowan Colliery was unveiled on Cardowan Road. Locals also hold a remembrance service every year to remember those who lost their lives in the industry on which modern-day Cardowan was built.

Ref: Cardowan Colliery Memorial. Photo: Kayleigh Hirst

Women’s Work

While the colliery provided the main employment opportunity for decades for Cardowan men, for women the options were narrower - with jobs in the pit canteen, or at the Black & White bottling plant in nearby Stepps among the few available.

Ref: Facebook: Cardowan colliery canteen in the 1970s.

Anne Symons moved to Cardowan with her family in 1968, and after commuting to Glasgow for several years to work, eventually got a job on the buses based out of the garage in Stepps. She remembers:

I went down to the garage on the Monday, and the boss gave me a form to fill in, which I did and gave him it back… I was going down to that garage every two weeks to get a job, and six weeks later, Mr Mullin was his name, he says to me ‘I’ve never known anybody as desperate for a job as what you are’ and he had a pile of application forms there about an inch, an inch and a half thick and he went down to near the middle one and he got my form out and he says ‘how would you like to start on Monday?’ I went ‘Are you kidding me on?’ and he went’ No, no’ and I went ‘Yes, yes’. So, he told me to be down at the garage on Monday morning for quarter to seven and see the duty inspector to get me my pass to take me from here through to Falkirk and back again.

The garage was down in Stepps where the Brewers [Fayre] is. That was Stepps garage and it went from the main road all the way. It was a good length, good length of buses there. And rather than just call it Stepps garage it took its name off the farm across the road, Gateside Farm, so Stepps garage became Gateside garage. That was a good place to work, you had a laugh, kidding and joking with them all and what have you. It was good.

Sandra Mackie also got a job in Stepps, when she turned 15 - at the Garfield Hotel:

My first job was in the Garfield, serving, doing silver service, function waitress for all of the weddings. Everybody in my family pretty much had worked in the Garfield. My mum’s side of the family and my dad’s side of the family. My gran worked in the Garfield, my Auntie Margaret worked in the Garfield, my dad, my uncle Jim worked in the Garfield, my Auntie Sadie who’s my mum’s sister, she worked in the Garfield, everybody! My cousin was a chef in the Garfield, we all worked there and everybody else in the area worked in the Garfield as well. It was when you were not quite 18 and you could go and get your first job. I started when I was 15 because I was too young to work the bar, you had to be 16 before you could table service for the bar so I was 15 when I started and 19 when I left.

The Cardowan Community

Life in Cardowan wasn’t just centred on work, however - it was a thriving community with a busy social life.

Anne Symons remembers:

The older folk, they had their club… the Parochial Hall. Anybody could go down there and a lot of the folk went down there to play bingo on a Thursday night. My mother and father being two of them, she was fairly lucky and everybody enjoyed that. And it gave the folk a chance to mingle with one another, and that’s exactly what they done. It would be my mother would walk in, ‘aw I haven’t seen you for a while, how have you been?’, that would let them get information like, the woman particular maybe hadn’t been well. Or somebody had maybe had a wean or what have you. And as I say, they all came together.

Sandra Mackie also remembers the feeling of growing up in a close-knit community:

Wasn’t any kind of crime at all, we never locked the door. I can remember if I went into the house and there was no-one in, you’d go in and you’d shout ‘hello!’, there was no answer and you’d think, ‘aw right OK, obviously my mum’s either across the back at her neighbour’s, or my dad’s down at the shop.

As a child, Carol Quinn remembers spending most of their time not far from her own doorstep:

We all just ran about, and it was always Cardowan, we never went venturing really to Muirhead or wherever. I mean, I think the furthest we ever went was maybe Stepps and back up the road. But we were always just up here, Tony’s Café, when you were old enough to go there… Cornfields, we spent a lot of time up the cornfields, up by Frankfield Loch where it is now, up the trees… see the garages, we spent a lot of our times up there as well, just sitting in the garages, and we would all play and we would go into the car park and play rounders or things like that.

Even as a teenager, Sandra Mackie recalls life centering on Cardowan:

I can remember I was 17 before I was allowed to go into town [Glasgow], as that was obviously the big city centre, but before that I didn’t want to go into town, I was quite happy climbing trees, just being outdoors. We were outdoors from noon, from morning, noon and night, you went back when you were hungry or when the rain came on. So being a teenager for me was not a typical teenager upbringing because I was just still happy out playing rather than being on the corner with maybe other people congregating, you know, having their odd can of strong lager. Being a teenager was still just great fun until I got my first job at the age of 15 in the Garfield.

Post-Industrial Cardowan

In the years since the closure of the mine, Cardowan has continued to change and evolve as it forges a new identity.

Despite Cardowan losing its main industry, and local job prospects still limited, recent years have seen increasing numbers of new houses being built in the area, including on the site of the former pit. Attracted by good transport links with Glasgow, with Stepps train station (which re-opened in 1989) just down the road, and not far from the M80 motorway, more and more people are making Cardowan their home.

For those that grew up here, however, the changes are not always welcome. Carol Quinn shared her feelings about how Cardowan has changed over the years:

I lived here in Cardowan - one way in, and one way back in and that’s what I loved about this wee village, it was over the bridge and back out the bridge. Now you can come in from different ends, house building, house building, the pit closing… The pit closed and they built all they houses there, Frankfield. That was brilliant, they fields were great, the cornfields, and it was all childhood memories. Houses there, it’s just surrounding… it’s boxing us in. Even they opened a train station didn’t they, we never had that when I was growing up.

Sandra Mackie also reflected on the changes she has seen since she was a child:

We used to play in the swamp, the swamp is now called Frankfield Loch, and people pay lots of money to buy a house and look at the swamp which we used to play in, which just still beggars belief!

Despite the increasing housebuilding, there has been an effort to conserve green space around Cardowan. The Cardowan Moss Nature Reserve was designated a local nature reserve in 2006 and is managed by Forestry and Land Scotland.

Locals also have taken it upon themselves to fight for the preservation of nature. The Cardowan Community Meadow group was started in 2019 by local residents to protect the area’s remaining green space from further housebuilding. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the group came into its own as they worked together to look after their community, providing food parcels and deliveries to vulnerable residents. Now, as well as maintaining the meadow space, which is home to a rich array of wildlife including deer, foxes, bats, owls, and hedgehogs, the group also provide activities for young people and organise a health and wellbeing group and active travel hub.

Ref: Cardowan Community Meadow.

View on Facebook

It is this community togetherness which many residents feel makes a place like Cardowan special. Sandra Mackie eventually moved to Moodiesburn, but feels Cardowan still has a strong community spirit:

I think communities like Cardowan, like Garthamlock literally just across the field, like Gartcosh, I think as a community they’re still very close knit, which is great. And I loved growing up there when I was wee, if there had been housing available for me to buy when I was in that position I would have stayed in the community because I would have wanted my kids to grow up with the same feeling of community, and the fact that you couldn’t get away with murder because everybody knew you, and knew who you were. Yes, I still feel that there is a community aspect in living in those areas.

Cardowan now has a Community Action Plan, developed in consultation with local residents, which sets out the vision for this small but growing community over the coming years. With the aim of improving transport links, amenities, and continuing to improve the green space and look of the village, it is hoped the plan will bring about positive developments to Cardowan.

From a tiny community centred around industry based on a private landowner’s estate, to a large and close-knit mining village, Cardowan is now carving a new identity for itself as those whose families have lived there for generations work to build a strong and thriving community of the future.