Easterhouse

Early Days

The area around modern-day Easterhouse was once a quiet, rural region. Like other communities around the Seven Lochs, Easterhouse was once part of lands owned by the Bishops of Glasgow, who used it for hunting, and rented out some of the space to tenant farmers.

Ref: Newly refurbished Provan Hall. Provan Hall Community Management Trust.

https://www.provanhall.org/

It is thought (although not known for sure) that the Bishops of Glasgow built Provan Hall in the 1460s. Provan Hall still stands today, in the centre of Auchinlea Park and neighboured on one side by Glasgow Fort shopping centre, and on the other by modern-day housing. There is some debate about whether Provan Hall may be Glasgow’s oldest house (although Provand’s Lordship near Glasgow Cathedral may also lay claim to that title). In any case, the house stood as the most prominent feature of the surrounding area for hundreds of years.

By the 18th century, the area had become a popular place for wealthy Glasgow merchants to build themselves country houses. They would buy land, much of which they often rented to farmers to give themselves an extra income, but some of which they kept to build fine mansions. One such mansion was Blairtummock House, which still stands today, and Easter House, which appears on maps as early as 1773, and may have given the modern-day area its name. It stood until the 1930s, near the area where the Easterhouse Phoenix sculpture now stands.

Ref: A map of 1755 shows Blairtummock and ‘E. House’ in the centre. The parallel hatched lines all around indicate farmland. National Library of Scotland.

https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/side-by-side/#zoom=14.6&lat=55.86429&lon=-4.10987&layers=4&right=osm

Around this time, farmers in the area were mainly growing flax. The plant was spun to make linen, and there were fields at Wellhouse where strips of linen fabric would be laid out to bleach. Weaving provided employment in the small villages in the area, with Swinton, West Maryston and Baillieston predominantly weaving villages. The coming of the Industrial Revolution and the introduction of mechanised looms meant the decline of the home weaving industry after 1830, in this and many other areas in which it had provided the main employment.

Coal

It was around this time that the area around modern-day Easterhouse began to attract new people due to the burgeoning coal mining industry. The Monklands area east of Glasgow had been found to be a rich source of coal, and the industry rapidly developed. The Monkland Canal was constructed in the 1770s to link up the Monklands coalfields with the fast-growing city. The route of the canal passed through the Easterhouse area (it was eventually filled in in the 1970s and became the route of the M8 motorway).

It is thought the first development of Easterhouse, from a farming community to a small village, came with the coming of the canal and the growth of the coal mining industry. Cottages were built to house people who worked on the canal, while others settled there to work as miners in a number of small coal pits that were sunk in the area. By 1840, the population of the district around Easterhouse was more than 1,200.

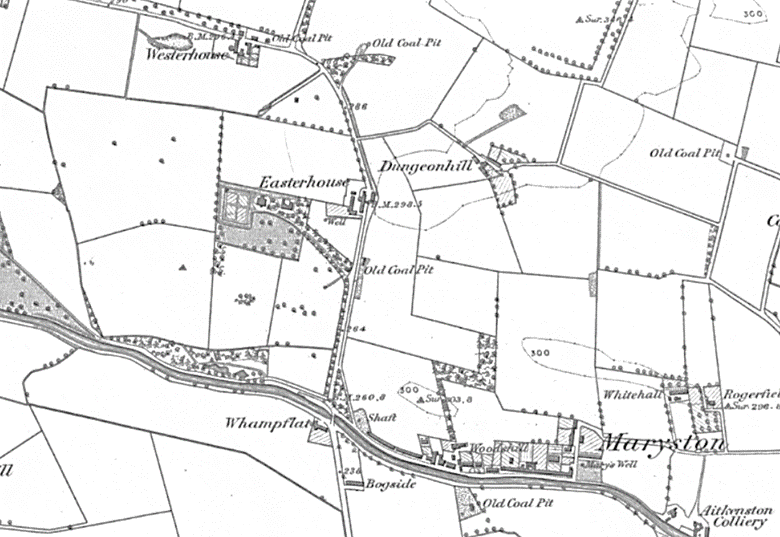

Ref: A map from the 1850s showing the farms of the Easterhouse area with several ‘old coal pits’ nearby. National Library of Scotland.

https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.5&lat=55.86525&lon=-4.10496&layers=257&b=1

Along with farming, coal mining remained the dominant industry in Easterhouse for the next hundred years. Writing in 1977, Mary Robertson, who grew up in Easterhouse village around the turn of the century, remembered a close-knit community where miners and their families worked together, and played together. The miners’ union would organise an annual trip to a seaside resort, with a local brass band known as the “Hole Baun” providing music for any functions held in the village.

The end of the First World War marked the start of the decline in the local coal mining industry, with strikes an increasingly common occurrence as workers fought for their livelihoods. Again, the community banded together, and were supported by local farmers who donated vegetables so the miners could make soup to feed their families, while the striking miners themselves scavenged scraps of coal from the bings in order to keep the soup boilers in action. The decline of mining around Easterhouse in the 1920s and 30s meant many were forced to look for employment elsewhere, with some travelling to Glasgow for work.

The legacy of Easterhouse’s once-busy coal industry resurfaced much later, when the first houses of the new scheme were being built in the 1950s. When digging foundations in Westerhouse Road, workmen struck coal, and it is said they helped themselves to the free fuel for three weeks! The existence of a valuable coal seam was also cited as a reason for the delays in building Easterhouse’s first (and much needed) shopping centre, until a public inquiry eventually decided one could be built on the site as originally intended - after years of delay.

Easterhouse Village

Before the coming of the new housing scheme, Easterhouse had been a busy village, with its heyday at the turn of the twentieth century. The village centred around rows of miners’ cottages either side of the road to the south of the canal. Easterhouse, along with neighbouring villages Swinton and West Maryston (known locally as ‘the Hole’), were served by the railway, with Easterhouse station having opened in 1871. The line connected the city of Glasgow with other railways in the Monklands, and meant those living in Easterhouse were able to travel to the city with ease.

The village had its own shops, with a branch of the Shettleston Co-op society, a Post Office, grocery store, sweet shop, and a pub (which still stands today, the Bridge Inn on Easterhouse Road). Around 300 children from Easterhouse, Swinton and West Maryston crossed the canal bridge every weekday to attend school on the north side, while many villagers worshipped at Bargeddie Parish Church, built in 1876, whose spire could be seen across the fields. In comparison to other villages, Easterhouse was considered slightly better off, as the houses were of the ‘room and kitchen’ type rather than the more common ‘single end’ (a basic one-room house).

The village was a favourite place for outings for people from the city. The Co-op ran an annual trip for children from the South Side of Glasgow, who would come in horse-drawn carts to Riddrie, then take a barge up the canal to Easterhouse for a picnic, while children from Coatbridge came on hay wagons to play games in the fields around the village.

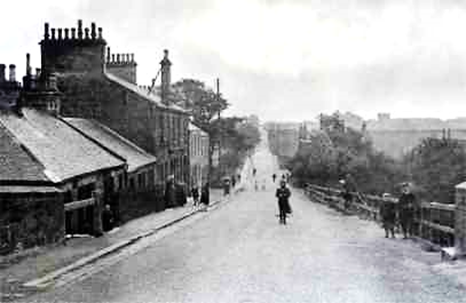

Ref: Old Easterhouse Village. Monklands Memories website (archived).

https://web.archive.org/web/20190118191538/www.monklands.co.uk/easterhouse/

Having enjoyed decades of peaceful existence, by the 1930s, Easterhouse village was in decline. The downturn in the local coal industry and the loss of many Easterhouse men during the First World War had devastated this small community.

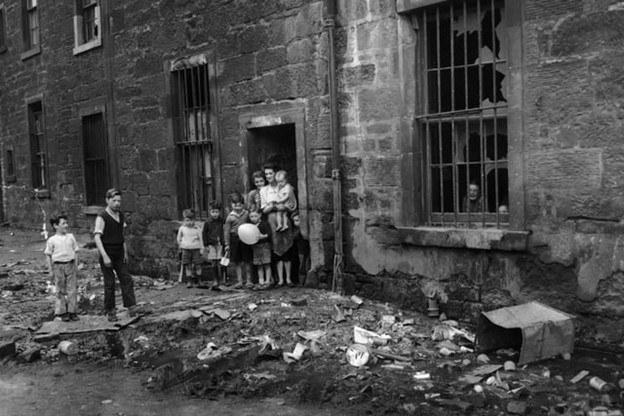

At the same time, the Corporation of the City of Glasgow had a major housing problem on its hands. Many of the city’s tenement homes built in the 19th century were falling into disrepair, and urban communities had become overcrowded, unsafe and unhealthy places to live.

Ref: Nicholson Street flats in the Gorbals, 1956. Glasgow World.

https://www.glasgowworld.com/news/people/transformation-of-the-gorbals-in-pictures-3469837?page=1

The Corporation planned to build thousands of new houses on the outskirts of the city, and as a first step towards this new future, in 1938 it absorbed Easterhouse (which had previously been part of the County of Lanark) within the boundaries of Glasgow City.

Building plans were interrupted by the Second World War, but soon after its end, work began to create new housing at Easterhouse that would see this formerly sleepy rural area eventually transformed into what some claimed to be Europe’s largest housing scheme.

While the new housing was intended to relocate people from overcrowded, inner-city parts of Glasgow, the Corporation also planned to move residents of Easterhouse village, rather than upgrade their miners’ cottages which, by 1950s standards, provided a very basic level of accommodation. While a few buildings of old Swinton and Easterhouse remain (including the Bridge Inn), rows of houses were marked for demolition, and West Maryston village was demolished completely. It is now the site of West Maryston woodlands, at the southern edge of modern-day Easterhouse.

New Easterhouse

Glasgow Corporation had annexed other outlying areas into the city as well as Easterhouse and began building housing in earnest in the early 1950s - first in Drumchapel (on the western edge of Glasgow) in 1952, followed quickly by Castlemilk (to the south of the city) in 1953.

At the same time, plans were in development for Easterhouse, with the Glasgow Herald reporting that alongside thousands of brand-new houses would be built schools, churches, swimming baths, a cinema and a pub. For those living in overcrowded, dilapidated tenements, the new schemes sounded like paradise.

Wellhouse was the first part of the Easterhouse scheme to be developed, south of the Monkland Canal and next to the Queenslie Industrial Estate, which had been opened six years previously. The name Wellhouse comes from Wellhouse Farm, which had been one of the only notable features of the area for the past two centuries. Indeed, many of the names used for parts of the growing scheme were taken from those of local farms, including Westerhouse, Netherhouse, Dungeonhill, Rogerfield, Greenwells, Commonhead, Queenslie, Blackfaulds, and Lochwood.

By the end of 1954, an army of workmen had moved into huts on Bartiebeith Road in Wellhouse, diggers had got to work - and the area would never be the same again. Over the following years, the scheme would grow rapidly, and as one section of new houses was completed, residents would move in to what amounted to a building site, as work continued on ever more new houses. Ian McLaughlin, whose mother-in-law was one of the first to move into Conisborough Road in 1958, said she recalled a constant battle against dirt being walked into the brand-new house, as pavements had not yet been laid down.

Alex Martin, writing in 1977, remembered the feverish comings and goings of families moving in, and workmen travelling back and forth, during these early, exciting years:

By the middle of 1958, the first four areas were completed […] and flittings [moving house] became the order of the day. At all hours of the day and night removal vans, coal lorries, and vehicles of varying type and size could be seen heading for the houses […] These vehicles were carrying all the worldly possessions of the homeless and overcrowded families from the city's central area, who after many wary years of waiting, had at last found their place in the promised land. Rivalling and far exceeding this fleet of vehicles were the convoys of high sided builders, lorries heading for the city centre each night between 4:30 and 5:30 in hail, rain, sunshine or snow filled with building workers all standing. In fact, it seemed that not one single man could have been squeezed into any lorry, so tightly where they packed.

Ref: Removal men move Glasgow residents to their new homes. Mungo’s Medals, 1961, National Library of Scotland.

https://movingimage.nls.uk/film/2102

The rate of construction was dizzying. 1,690 homes were built in Wellhouse; these would be followed in quick succession by 608 more in Queenslie, 1,333 in Easterhouse, 986 in Provanhall, 2,221 in Lochwood, 1,077 in Rogerfield, 531 in Hallhill and 666 in Blairtummock - all within the space of five years. In less than a decade, Easterhouse had transformed from a small rural village surrounded by farmland, to a community of more than 40,000 people.

Ref: Flats at Duntarvie Quadrant, Easterhouse, pictured in 1959. Glasgow Story.

https://www.theglasgowstory.com/image/?inum=TGSA00796

All this construction came as a shock to the farmers who continued to live and work around Easterhouse; the encroachment of new buildings up to the edge of their land, and tens of thousands of incomers, was startling. One farmer, Mr Lyle, had worked Heatheryknowe farm, on the eastern edge of the new scheme, since the 1940s. He complained that children moving into the new houses broke down his fences and disturbed his cattle and hens. Another farmer reported 100 of his hens stolen one evening - they were found with their heads chopped off in a field the next day.

For the children themselves, moving from cramped urban conditions to the “countryside” must have felt like living in a giant playground. Though a minority may have caused damage to property, most engaged in much lower-level mischief, including stealing turnips to make lanterns at Halloween, or taking sticks of rhubarb from the edge of the field to dip into a bag of sugar.

For adults moving to Easterhouse too, the new houses were a huge improvement on the conditions they left behind. With more space, their own balconies, and indoor bathrooms, the new flats seemed luxurious by comparison to crumbling tenements. Ann McKenna, writing in 2002, recalled:

I remember the day we moved into Easterhouse. While the flitting was still going on, my older sister stripped me and my young sister and put us in the bath. We had never seen a bath in a house before and we thought it was our very own indoor swimming pool.

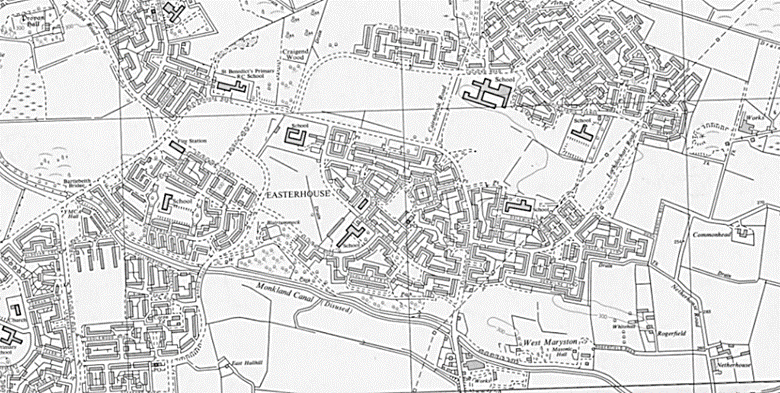

Ref: A map of the area from the 1960s, showing blocks of new housing. National Library of Scotland.

https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=14.9&lat=55.86719&lon=-4.11597&layers=193&b=1

The optimism and pride of Glasgow Corporation in creating the scheme at Easterhouse was apparent when they chose to celebrate a flat in Carriden Place as the 100,000th house to be built in the city since the end of the First World War.

But this optimism would prove to be short lived. The speed at which the new houses had been built, and the lack of planning for the needs of an enormous and diverse community, quickly created problems.

Reality Kicks In

With an urgent demand for housing after the Second World War, many of the new flats in Easterhouse and other parts of Glasgow were created from materials that were cheaper and easier to come by, and quicker to build with: walls were made from concrete blocks, and window frames from metal. But this made the new houses more prone to damp, and much more expensive to keep warm.

The damp and cold created a vicious circle for residents - the damper and colder they got, the more expensive they were to heat - and their condition deteriorated rapidly. By the mid-1960s, with most housing having stood for less than ten years, a survey of residents showed many unhappy with their living conditions. 60% felt their house was not well designed, 61% said they were built with poor workmanship, and 53% said their rooms were too small - this after only recently moving from much more cramped conditions.

By the time the initial influx of new residents to Easterhouse had slowed, many people were already choosing to move out of the area. Their vacant flats were even at this time proving difficult to re-let, and much of the new housing entered a cycle of abandonment and worsening conditions.

On top of difficulties with the housing stock, the new residents of Easterhouse were having to cope with a brand-new way of life in a remote part of the city, torn from their friends, family and neighbours. The new community was made up of people who had lived for generations in the East End, the City Centre, the South Side, or the north of the city, taken from their familiar surroundings and support networks and thrown together for the first time.

Work was also hard to come by. When building the new housing scheme, Glasgow Corporation had hoped industry would naturally follow to exploit this new and abundant workforce and provide local jobs. But that hope did not happen, with the reality being new residents of Easterhouse now faced lengthy commutes to work at the jobs they had held in the city before moving away. Most men in the new scheme worked in the trades - as drivers, labourers, fitters, engineers, joiners or plumbers - while women were employed as shop assistants, cleaners, clerks or machinists.

In the mid-1960s, less than 5% of those who lived in Easterhouse worked locally. Some of those lucky enough not to have to commute worked at nearby Queenslie Industrial Estate. Brian Toland lived in Garthamlock and remembers the businesses based there:

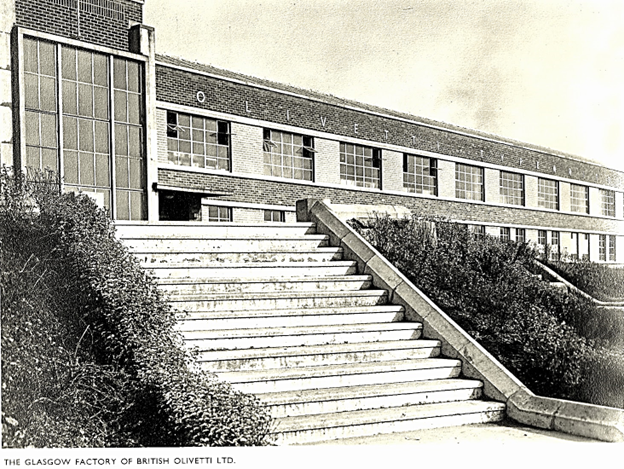

Queenslie Industrial Estate you had engineering, labelling manufacturers, manufacturers of making beds, deliveries, foods, warehousing, knitwear factories, coat factories, shirt-makers. All they were all in a straight [line]. Olivetti made typewriters, they were one of the biggest, they had a big, massive factory going right along the end of the road the full length of Queenslie Industrial Estate was Olivetti. Then you had all your wee units behind it, all the way up the hill. They even had a big canteen in there for all the workers who could go over at dinner time and have their dinner. And then from four o’clock all the buses would be sitting waiting for all the people to take them back down the road to where they were going to.

Ref: Olivetti Typewriter Factory, date unknown.

oz.Typewriter: Inside the Olivetti Typewriter Factory, Glasgow, Scotland (oztypewriter.blogspot.com)

Queenslie Industrial Estate aside, employment options were limited, and with few households owning a car, many faced lengthy commutes by bus back to Glasgow for work. Not that the local bus service was very convenient or reliable. Glasgow Corporation, which ran bus services all across the city, only started a service to Easterhouse in 1957 - two years after the first houses were built - and then, just one route. Commuters had to rely on private bus companies, but with tens of thousands of people leaving their houses and returning home at the same time, the service was far from adequate. Residents also recall the bus terminus moving further and further away as more and more houses were completed on the scheme.

As well as having no local work, the first families to move to Easterhouse had no local schools, with the first primary school only opening in 1959. Alex Martin remembers:

During these three years, almost every child in Easterhouse was being educated outside of Easterhouse, most of them far outside. Many were transported by special buses to old schools in the oldest of the East End schools […] This daily exodus of many thousands of children caused much upset and heartache and I do not think anyone could be happy about it all, except the companies who supplied the special buses. Firstly, the buses left Easterhouse 8:30am summer and winter alike. This meant half an hour earlier start than normal for all children. Further, children who had returned home for their lunch previously had either to carry sandwiches or attend dinner school (at the expense of their parents, not the education authority) if their father was in employment.

Other amenities were also scarce in this new community. Before shops opened in Easterhouse, residents had to travel back in to Glasgow for their groceries, or pay over the odds for goods from mobile vans that had sprung up to fill a gap in the market. One local resident remembers:

There was the milk van that also had bakery products, ice cream vans and a fruit and veg van that went round the scheme. Bells, whistles and jingles sounded at all different times of the day. ‘Quick - or yeez’ll miss the van!’ was the cry then. There were static vans too that sold everything that the most modern houses might need. All with top prices of course and the always important ‘tick’ or ‘slate’ to encourage debt for the most unwary. These vans were just like the corner shop and open all hours.

Ref: A mobile van shop doing the rounds in Easterhouse: ‘Glasgow Memories - the East End’, Peter Savage/ Glasgow Heritage Group, 2013.

Parks were also a rarity, and the council’s plans for developing proper play areas and green spaces didn’t sound that ambitious, with Glasgow Corporation’s Superintendent of Parks explaining that in future, “the spare bits of ground which are all grass just now will have seats round the outside”.

With a population of more than 40,000 by the early 1960s (more than that of present-day Stirling), Easterhouse was served by only three doctors and one dentist. Neither the swimming pool nor cinema touted in the Glasgow Herald as being part of the plans for the scheme had materialised; neither was there a library. There was no shopping centre, no banks, no community centre - and no police station.

With many residents by this time choosing to move away from their new houses, some even returning to the areas they had just left, those who stayed behind had to do their best in a community that was to face significant challenges in coming years.

Difficult Times

Some of the challenges faced by the new community of Easterhouse would contribute to problems that became deep-seated over the next few decades.

A lack of employment and opportunities for young people, and the absence of social cohesion in this brand-new community, led to problems with youth delinquency and gang violence as early as the 1960s. Rival gangs would fight to protect territory, carving out the new scheme into areas of control and effectively creating ‘no-go’ zones across the area. Violence, and knife crime in particular, was becoming an increasingly fraught problem. All this was happening in an area that had no local police presence - the first police station didn’t open in Easterhouse until 1965.

By the late 1960s Easterhouse already had such a reputation for violence that it came to the attention of one of the biggest celebrities of the day, singer Frankie Vaughan, who read about the community’s problems in the press, and decided he wanted to help. Having had brushes with gang involvement in his youth, Vaughan knew the dangers Easterhouse’s young men were being exposed to and wanted to use his influence to bring about peace between warring gangs.

In 1968, after a hot summer when violence had reached even higher proportions than usual, Frankie Vaughan visited Easterhouse to call for a weapons amnesty. The visit attracted huge publicity, and although well-intentioned, had the unforeseen consequence of cementing Easterhouse’s reputation for violence in the popular imagination - a reputation it would struggle to shake for years to come.

Frankie Vaughan’s intervention led to the foundation of the Easterhouse Project - a plan to build a dedicated youth centre to give the community’s teenagers somewhere to go, and something to do. It got off to an inauspicious start. The Army was called in to build a temporary youth centre from two former Nissen huts, but a dance held to raise funds had to be called off at the last minute when officials found the fire doors at the rear opened on to a five-foot-deep drainage ditch. Frankie Vaughan had planned to attend the opening ceremony but had to cancel his trip. The building was beset by problems, with vandalism a regular occurrence, while Glasgow Corporation’s less than enthusiastic support for the project saw it withdraw funding at regular intervals.

Ref: Easterhouse Project. Generation Easterhouse Oral History Project.

https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=401552025469597&set=a.401552008802932

Nevertheless, those who grew up in Easterhouse in later years remember it being a well-used space for young people, as originally intended. Tracy Smart grew up in Easterhouse in the 1980s and remembers:

On a Saturday, we used to go to The Project, it was behind St Leonards Secondary School and it was like the half dome, they were like corrugated domes, like really long. And it was a disco, every Friday and Saturday night, you used to have the younger one and after that you’d have the older one and we used to go to them every Friday or Saturday.

Community Action

While Easterhouse faced its share of problems, the late 1960s was also a time that saw parts of the community come together to improve things - and that meant doing things themselves. Like the coal mining families that had settled in the area decades before, folk in Easterhouse banded together to support each other, improve their community, and make their own entertainment.

With a lack of built amenities, Easterhouse residents set up a drama club and an old people’s club, while the YMCA hosted other activities including a popular football team. When long-awaited schools were eventually built, it created space for evening groups, country dances and activities for young people.

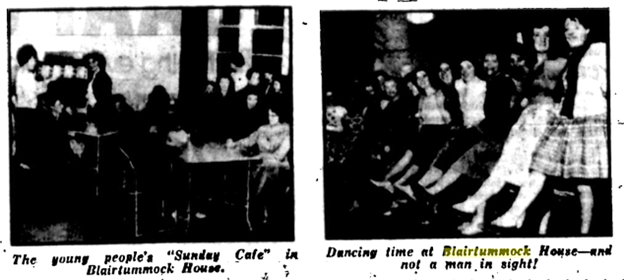

The community also took on the running of Blairtummock House, the former merchant’s mansion, which had been bought by Glasgow Corporation in 1955 with the intention of knocking it down to replace it with a bowling green, tenpin bowling alleys and tennis courts. The Corporation never came good on its plans, and by 1965 the building had been condemned.

Having lain derelict for decades, the community took the house on, using it for dances and bingo, and renting out space to the local Labour Party. By 1968, after some renovation, the house was re-opened as a community centre and became home to the council’s new social work department. (After a subsequent period of dereliction in more recent years, the house has now been fully refurbished and is home to a children’s play centre.)

Ref: Activities at Blairtummock House. Image taken from Evening Times, 11 May 1961.

Local residents also began to form themselves into associations to work together to improve things for their community. In 1967, the Easterhouse Community Development Committee started to bring together representatives of various tenants’ associations in the area. The Committee organised Easterhouse Community Weeks, held in 1969 and 1971, bringing the residents together across a week of free shows and activities, including a parade to crown the Easterhouse Queen.

The Development Committee also campaigned for the construction of a shopping centre and other amenities, and soon their hard work began to bear fruit. A temporary library was erected in 1968 (a permanent one would follow in 1971), work started on a swimming pool in 1969, and in the same year, work beginning on a new ‘Township Centre’, that would house Easterhouse’s first shopping precinct (it would later become Shandwick Square and is now known as The Lochs).

With the first residents now having now lived in Easterhouse for more than 10 years, the shopping centre was much welcomed. The first shops (a wool shop, chemist and supermarket) opened just before Christmas 1971, and were quickly followed by a branch of the Shettleston Co-op. Having once been infamous for its lack of shops, Easterhouse was now home to the latest innovation in retail - the centre was the first fully enclosed air-conditioned mall in Scotland.

The Township Centre in which the mall sat was also home to a savings bank, Post Office, fish and chip shop, launderette, two pubs, a job centre - and later, a Citizens Advice Bureau (following a campaign by local residents, who emphasised the demand for this service rather than the originally proposed bingo hall). It quickly became the new heart of the community which, unlike long-established towns that had grown around a historic centre, until this time had lacked a focal point. Alex Martin recalled:

It is a joke between my wife and other friends that if you want to meet some other Easterhouse person you know, all you have to do is make for the shopping mall, take a seat and wait. Sooner or later, since everyone passes through, the acquaintances you seek will make their appearance.

Ref: Easterhouse shopping centre: The Writing on the Wall: new images of Easterhouse, Ron Ferguson, 1977.

Easterhouse in the 1970s

With more amenities now starting to be built, Easterhouse also saw more new houses added to the scheme, even as many existing flats lay empty. As people continued to leave the area due to ongoing social problems, it is thought that Easterhouse had 34 times the number of empty houses as other schemes of a similar size. Still, pressure to create new housing remained, and gap sites were filled with new flats even as others remained vacant nearby.

Born in the area in 1975, Tracy Smart remembers Easterhouse as a close-knit community at this time:

[We had a] two bedroomed flat, one up and it was just two bedrooms, kitchen, toilet, living room. And it was a brilliant flat, absolutely brilliant, we knew all the neighbours, everybody knew us, but it wasn’t one of the ones you’d talk about, nothing like that but it was a brilliant square, like the kids all used to come out and play.

"Everybody helped each other, if somebody needed something, there was always, like when my mum had my little sister, everybody was always at the door, 'Can we take the baby out? Can we take the baby out?', 'Take her, on you go.' So, there was always somebody, anybody needed anything, there was always someone to ask.

Despite the closeness of the community, Easterhouse was struggling against its entrenched reputation, and in 1972 Glasgow Corporation proposed breaking up the Easterhouse scheme into ten separate districts, each with a new name. The aim was to move away from the negative connotations of “Easterhouse” and to foster closer community connections by creating a tenants’ association in each of the ten areas, thus “helping residents to help themselves”. The Corporation hoped that locals would work together to tackle issues such as litter, untidy gardens, the condition of shared closes, and vandalism - giving them a sense of local pride but also helping the council surmount these long-running problems.

Thus, Easterhouse was divided into Queenslie, Provanhall, Bishop Loch, Commonhead, Lochend, Kildermorie, Blairtummock, Rogerfield, Wellhouse, and Easthall. The names were chosen for their local historical connections, many of them the names of old houses or farms that had existed in the area prior to the building of the scheme.

The 1970s also saw change come to Easterhouse in the form of the M8 motorway. Originally called the Monkland Motorway, the name is a clue that it was built on the route of the former Monkland canal, that old trade route that had taken coal from the Monklands into Glasgow two hundred years earlier.

By this time, the canal was disused and overgrown, and creating the new motorway was part of plans to turn Glasgow into a modern city - the same plans that had led to the building of Easterhouse and other schemes. Where the canal had flowed quietly through the area for two centuries, the motorway would create a new, much harder border separating much of the scheme from its former neighbouring communities around old Easterhouse village and Swinton.

Ref: The recently opened M8, looking north to Kildermorie Road, 1980. Canmore.

https://canmore.org.uk/collection/1554224

While work on the motorway continued in the late 1970s, Auchinlea Park was also being developed. It was described at the time as providing “much needed lungs for the Easterhouse area”. This green space, surrounding the historic Provan Hall, was nearly disrupted by plans to build a trunk road right through the middle to connect the new M8 to the A80. Thankfully that route never came to pass, and Provan Hall and the park remained undisturbed.

1980s

Already suffering social problems, Easterhouse continued to struggle on through the 1980s as Britain entered recession and saw its highest periods of unemployment in decades. This affected communities across the country but had a particularly bad impact in areas like Glasgow which were seeing the demise of heavy industry that once provided reliable jobs.

By 1983, three of Easterhouse’s largest employers, including Olivetti Typewriters, had closed. That year unemployment in greater Easterhouse was the highest in Strathclyde, with four out of ten men out of work. The loss of local jobs was also damaging for women, who were more likely to work part time and so found the cost of travelling to work elsewhere not worthwhile.

Tracy Smart remembers her mum struggling to find work:

Jobs, nobody could get a job, it was really hard, I can remember it, like struggling. Cause my mum was out of work after my sister was born and it was hard to get back into work, I think. That was the main… what I can remember at that time, cause I was only little.

By this time derelict and uninhabitable housing in Easterhouse was rife, with one in eight homes empty. Glasgow Council began a period of demolition, renovation and refurbishment to replace blocks of flats with smaller detached and semi-detatched houses.

Those still living in the run-down houses wanted to make sure they were moved to better accommodation, as Tracy Smart remembers:

One of the ones who stayed in Tina’s close, we called him Uncle Grubber, he was the last one to leave Canonbie Street. He refused to leave until he got the house that he wanted. And he eventually got the house that he wanted, he was the only person in this street, everything else was all boarded up, he was the last one standing until he got what he wanted, and he did get it.

Ref: Dungeonhill Road and Lochdochart Street, 1950s housing boarded up before demolition, 1981. Canmore.

https://canmore.org.uk/collection/2539225

Despite the problems, locals remember the late 1970s and 1980s as a time of strong community action in Easterhouse, with groups of residents taking control of vacant and disused buildings to start new services. Flats were converted into commercial premises, a vacant annex at Garthamlock Primary was turned into workshops, and other housing in Lochend became a community centre.

A group of locals led by Betty McPhearson also took up residence in a vacant shop, to open a cafe and provide activities for young people. The cafe proved particularly popular with builders working on the housing redevelopment, but eventually the shop was also earmarked for demolition as part of this work. Their eviction from the premises prompted the group, which by now also included Bob Holman (who’d go on to become a leading figure in Easterhouse’s regeneration) to set up a new organisation, Family Action Rogerfield and Easterhouse (FARE).

By 1989, FARE was able to rent a tenement block of six flats to serve as their headquarters. They focused on providing much-needed services, including sports classes, friendship groups, breakfast clubs, crèches and leisure sessions. FARE would go on to become one of the longest-established community projects in Easterhouse. It is now a registered charity working with disadvantaged communities across all of Central Scotland, although it’s still headquartered in Easterhouse.

Ref: FARE’s headquarters on Drumlanrig Avenue.

About — FARE Scotland (fare-scotland.org)

Recent Times

As the community of Easterhouse now enters its eighth decade, it continues to build on the positive changes of more recent times.

Throughout the 1990s, alongside FARE, a number of other community groups worked to tackle some of Easterhouse’s long-standing problems. The Phoenix Community Centre, Gladiators, and the Greater Easterhouse Alcohol Awareness Programme (GEAAP) have all worked to create services and provide help for the community.

The 1990s also saw the development of several local Housing Associations, which transferred responsibility for letting out and maintaining houses from the city council into the hands of local people, with each Association governed by a board of local tenants. The Housing Associations, including Provanhall, Wellhouse, Easthall Park, and Blairtummock, have given residents much greater control over their neighbourhoods, and have not only hugely improved the housing stock in the area, but also provided a range of other services and support to local residents.

Having suffered neglect and under-investment from the outset, the new millennium saw a wave of public and private spending in Easterhouse. This optimism was captured by a new public art installation, commissioned in 2001 by Blairtummock Residents’ Association. Sculptor Andy Scott’s Phoenix represents the community’s rise from difficult beginnings to a new future, and sits proudly at the eastern edge of Easterhouse, welcoming residents and visitors on their approach.

Ref: Easterhouse Phoenix by Andy Scott. Photo by Chris Upson.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Phoenix_in_Easterhouse_-_geograph.org.uk_-_128690.jpg

In 2001, John Wheatley College, which had been founded in 1989 to provide education in the communities of Shettleston, Haghill and Easterhouse, opened a new campus on Wardie Road to provide a home for the students who up until then had attended courses in an old school building.

The same year, planning consent was granted for a new retail development - Glasgow Fort - that would open in 2004. By 2014 this had created 2,500 jobs, with a significant number of workers coming from the local area. Further investment came with the opening of the Bridge centre in 2006. Home to a dedicated arts facility, Platform, the Bridge also houses the swimming pool and library. The innovative modern building was awarded Best Public Building at the 2007 Scottish Design Awards.

Ref: The Bridge. Glasgow Life.

https://www.glasgowlife.org.uk/libraries/venues/library-at-the-bridge

Easterhouse residents consulted recently feel there is still a lack of varied employment in the area, and local amenities and transport links need further improvement.

Tracy Smart shared her views of opportunities for younger people:

There’s different types [of work] but there’s less as well, it’s a lot harder to get a job nowadays. My 23-year-old, I think she was three years before she actually got a wee part time job.

Over the past few years, there has been increasing community involvement in changes within Easterhouse, particularly with government initiatives like the Thriving Places approach striving to involve local residents in decisions about their community. Having for decades been seen as an undesirable place to live, positive changes in Easterhouse have meant it is now attracting private investment, with new housing being developed in the green spaces at the edge of the existing housing.

From a rural farming area to a village built on coal mining, an experimental housing project to a reshaped - and reshaping - community, Easterhouse has changed dramatically over the years. Through bad times and good, Easterhouse as a community has always built itself on the hard work and spirit of the people who call it home.

As Tracy Smart says: “It’s the people that make [this area]. It’s the people who have been here all these years.”