Gartcosh

The community of Gartcosh has sometimes been called “a place with no history”, although you don’t have to look far to find out there is no foundation to this myth. Though it is true the place was a sleepy farming community until the arrival of industry in the mid-19th century, modern day residents of the village have almost two centuries of rich heritage to explore. And as we shall see, the area has an even longer history than that, with evidence of early settlements dating back around 2,500 years.

Early Days

The name ‘Gartcosh’ itself is thought to derive from the Gaelic ‘Gart’ meaning field, and ‘Cos’ meaning hollow. The label is an accurate description of an early settlement that may have been a forest clearing amongst the gentle hills of the surrounding countryside.

Indeed, evidence of early settlement in the area was found when work to build Gartcosh House began in the 1880s. Builders excavating the foundations for the house unearthed a dugout canoe, a simple vessel used by people in the Iron Age (around 700 - 100 BCE) to navigate waterways. Evidence of crannogs - wooden houses built on stilts in lochs, dating from the same era - were found around the same time at nearby Bishop’s Loch and Lochend Loch. We can only speculate that the canoe found right next to the Bothlin Burn in Gartcosh may have been used by these early water dwellers.

By the 1400s the land around Gartcosh was owned by the Bishops of Glasgow, who built a stately palace at Lochwood, between present day Gartcosh and the Bishop’s Loch. The surrounding land was very fertile and made for excellent farmland, so provided a good income for the Bishops in rents, while the abundant forests and lochs teeming with wildlife also meant the area was a valuable hunting ground.

Ref: A map from 1750 showing ‘Gartcaish’ in the centre, north of Bishop’s Loch. National Library of Scotland.

Development Of The Village

Though it had been a quiet farming community, the character of Gartcosh was to change dramatically with the coming of the railway, which would bring industry to the area.

One of the first railways in Scotland, the Glasgow to Garnkirk Railway, began construction in 1827. It was designed to link up the fast-growing city of Glasgow with the Monklands area and its burgeoning coal mining industry. The line ran right through Gartcosh, and on its opening day in 1831 famed engineer and “father of the railways” George Stephenson drove an engine from St Rollox through Gartcosh on the way to Gartsherrie and back again. At the same time, a locomotive ran in the opposite direction pulling minerals and grain, to demonstrate to excited spectators that the line was for both passengers and goods.

Ref: A painting by David Octavius Hill showing two locomotives passing each other on the opening day of the Glasgow Garnkirk Railway. The Glasgow Story.

https://www.theglasgowstory.com/image/?inum=TGSA01138

A stop was opened at Gartcosh in 1837 - although not a station as we know it today, as there were no platforms or waiting rooms. By 1846 the line had been taken over by the Caledonian Railway, which meant that all trains coming to Glasgow from other cities in Britain had to first pass through Gartcosh.

From a Victorian industrialist’s point of view, easy access to the railway now made Gartcosh an ideal place to set up shop. First to be built was an iron works, followed shortly by a brickworks, which brought labourers to the area and would see the village begin to grow at speed.

Iron Works

Attracted by the railway, William Gray & Company set up the Woodneuk Iron Works in Gartcosh in 1865. The works had 12 furnaces and worked with iron ore that had already been processed into a crude product known as pig iron, refining it into the more valuable malleable wrought iron. The works had a rolling mill that would roll this iron into thin sheets, which would then elsewhere be made into items like rivets, nuts and bolts, nails, wire, chains, water and steam pipes, horseshoes, and items for the railways - industrial products very much in demand at this time.

This was skilled work that was new to the area, and so the owners had to look elsewhere to employ the labourers they needed. Thus, the village of Gartcosh began to be settled by Welsh and English workers who had moved north from Shropshire, Staffordshire, Derbyshire, Warwickshire, Worcestershire, as well as south Wales, where iron and steel making had already developed. Even today, many families in Gartcosh have English and Welsh surnames, generations on from their relatives who came to settle in the area.

Ref: Smith & McLean staff group, pictured in 1935. East Dunbartonshire Archives

Despite the influx of workers and the proximity to the railway, the works seems to have struggled in its first years, being bought out in 1866 and again in 1867. It was finally acquired by Smith & McLean in 1872, when it began to prosper.

Over the decades, the iron works would adapt and take on the manufacture of steel, a relatively new industry that quickly outpaced ironmaking. Steel was stronger, tougher and was becoming increasingly cheaper to make - and was much in demand from the Clyde shipbuilding industry. Eventually steelmaking would become the dominant industry in Gartcosh - but more on that later.

Brickworks

Around the same time as the iron works and attracted by both the railway and the fact the area was rich in clay, a brickworks was established at Gartcosh. Along with other brickworks in neighbouring communities like Heathfield, Garnkirk and Glenboig, the industry soon established itself, taking advantage of the abundant clay soils that lay not far below the surface, which meant this natural resource was relatively easy and cheap to dig up and turn into other products.

Though smaller than other brickworks in the area, Gartcosh made a wide variety of products including firebrick (a special type of hard-wearing brick used in industry as it could withstand high heat), as well as garden vases and ornaments, fountains, chimney pots, roof tiles, cattle troughs and sewage pipes.

The area around Gartcosh and Glenboig soon built a reputation for good quality products, and was at one time the world’s largest producer of fireclay bricks. Individual bricks were stamped with the name of the place they had been manufactured, so Gartcosh bricks were easily identifiable. The works were bought by the Glenboig Union Fire Clay Company in 1890, though they retained the Gartcosh brand. Thanks to their reputation, the bricks made in this area were exported for use around the world, and ‘Gartcosh’ brand bricks are still found today in far-flung locations.

Ref: A Gartcosh brick found in Queensland, Australia. Scottish Brick History.

https://www.scottishbrickhistory.co.uk/gartcosh-30/

Interviewed in 2023, local resident Liz Ward explains that the brick industry in the area has given Gartcosh locals and sense of pride about their heritage:

The Gartcosh [bricks] have been found literally all over the world, we’ve got stories from people who have been in the Bahamas and Barbados and all the rest and they found them on their pathways. People over there pay quite a lot of money to get them put on their pathways and their patios and all that, so they’ve got the Glenboig and Gartcosh ones, and we are seeing pictures of them. Also, one was found in Hawaii, the Gartcosh and more recently Glenboig one, at the bottom of the ocean, and we heard about that one and that was near Pearl Harbour, so it is actually incredible where they got to.

After a busy few decades, the Gartcosh brickworks closed in the 1920s as the industry faced competition from elsewhere and struggled to keep up with new manufacturing techniques. The works were re-opened on a smaller scale in the 1930s with around half the original number of workers. Production continued until the 1950s when fireclay supplies in the area were exhausted, and the Gartcosh works, along with other brickworks in Glenboig and elsewhere, closed for good.

The Gartcosh works were demolished in the 1960s, and the site is now home to the Redrow-built houses of Heathfield Park Estate.

Life In Industrial Gartcosh

The coming of the ironworks and brickworks meant the population of Gartcosh began to grow. Around 350 people lived in the area in 1881, but this doubled over the next 20 years as more and more people moved there for work and began raising families.

When Smith & McLean took over the ironworks in 1872, they decided to build new houses to replace the dilapidated buildings the workers had been living in right next to the works. The houses (known as ‘the Buildings’), were built near Lochend Road, half way between the ironworks and brickworks. They all had one living room, one bedroom, one kitchen and an inside toilet. Two of the streets where these new houses were built were named after the works’ new owners as they put their stamp on the village - Smith Terrace and McLean Place.

Ref: ‘The Buildings’, 1978. Canmore.

https://canmore.org.uk/collection/549456

To serve the local residents, a mission hall and a church were erected - this was an Episcopal church, to serve the predominantly English workers who lived there at the time. Smith & McLean also built a cottage to house the nurse who tended to the iron workers - this is Memorial Cottage on Lochend Road and is still known locally as the Nurse’s Cottage.

Ref: Memorial Cottage (nurse’s cottage), Gartcosh, 1978. Canmore.

https://canmore.org.uk/collection/549520

All this development meant Gartcosh was becoming a busy, noisy place. What once had been green fields was now taken up with heavy industry, stock yards, railway sidings and buildings, and the comings and goings of hundreds of labourers.

While the iron and brickworks were the dominant employers in Gartcosh, some people travelled to Glasgow for work, or were employed as nurses, caretakers and in other roles at nearby Gartloch Hospital. The hospital was opened as the Gartloch District Asylum in 1896 and at one time housed around 800 patients. Although primarily a psychiatric facility for people deemed to have mental health conditions, the hospital served other patients including those with tuberculosis, for whom a separate ward was built, and during the Second World War was used as an emergency medical services hospital.

Life in Gartcosh was also controlled by the wishes of the local landowners, the Hill sisters, strict Presbyterians who were not keen for Smith & McLean to expand their ironworks. They eventually relented, but only on the condition that no betting shop, pub or Catholic church could be built in Gartcosh. Without its own pub, Gartcosh’s nearest place to get a drink was Chapman’s, just outwith the village boundary on the other side of the Bothlin Burn. It still stands today, though now separated from the village by an even harder boundary, the M73 motorway.

Ref: Chapman’s pub, Gartcosh. Old Glasgow Pubs.

https://www.oldglasgowpubs.co.uk/robert%20chapman.html

One Gartcosh resident remembered a particular manager at the ironworks, James Bryden, a strict teetotaller who ruled with an iron fist from the 1930s to the 1960s. He lived next door to Chapman’s and would take the names of workers he saw passing his window on their way to the pub. Any workers he caught would be summoned to his office on Monday morning and warned they would be sacked if they were seen at the pub again. As workers’ houses were owned by the company, losing your job also meant you and your family being evicted from your home, so this was a serious matter. Workers found ingenious ways around this threat, either catching the bus for the 300-yard journey from the village to the pub, thereby escaping notice, or sending their children to have screw-top bottles filled at the bar.

The Hill sisters’ rules still abide in Gartcosh today - there has never been a Catholic church or betting shop in the village, nor a pub within the boundaries (though the Gartcosh Works Social Club was granted a licence to sell alcohol in the 1960s).

School

A new law was introduced in 1872 that meant all children in Scotland between the ages of five and 13 had to be educated, and so with a growing population, Gartcosh built its first school in 1875.

With the village still being a fairly isolated place at this time, a schoolhouse was built next door to serve as a home for the headteacher, so they would not have to commute to work. The school was knocked down in 1911 and rebuilt two years later, but it is this building which still serves Gartcosh primary pupils today, more than 110 years on.

Ref: Gartcosh School, pictured 1978. Canmore.

https://canmore.org.uk/collection/549452

Liz Ward was a teacher at the school when she moved to Gartcosh in the 1970s. She remembered:

There was still the hall at the top of the road, the wee school next door. The whole staff and the whole school, you could actually sit on the steps of the school, it was tiny! I think there was about 40 children in that school, that’s all there was, from primary 1 all the way to primary 7, it was tiny. You would hardly know there was anybody in there, so there was no problem being a teacher and staying next door to the school, you could hardly hear them. It was unreal. In fact, I actually had wanted to be headteacher next door, I thought it would be quite a good job, being next door - do the washing, hang it out, nip in next door again. Never happened, but never mind!

The whole of Gartcosh Primary School pupils and staff - date unknown. Gartcosh Local History Group.

View on Facebook

Shops

The community was well served by local shops and businesses. The Brownsland building at the bottom of Lochend Road was built in the 1850s as a shop with flats above, and would become home to a butcher's, shoe repair shop and small general goods store, as well as DiNardo’s fish and chip shop. Frank DiNardo had arrived in Gartcosh from Italy in 1900 and established his fish and chip business which would remain in his family for generations. Sadly, the Brownsland building was demolished in the 1960s to make way for the M73 motorway.

Gartcosh also had its own Co-op, with a butcher, grocer and drapery. The building originally had its own hayloft and stables, used when milk would have been delivered by horse and cart.

Ref: Gartcosh Co-op, 1918. Image from East Dunbartonshire Archives

The building still stands on the corner of Lochend Road and Old Gartloch Road (though the hayloft and stables have since been demolished), and is now home to a pharmacy, hairdresser, corner shop and takeaway.

Ref: Gartcosh shops, formerly the Co-op, pictured 1978. Canmore.

https://canmore.org.uk/collection/549518

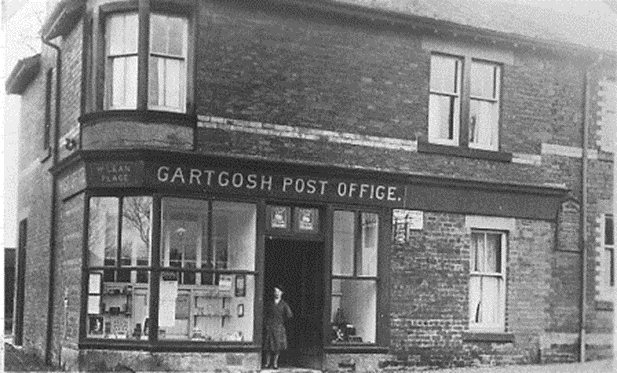

Near the Brownsland building was the village Post Office, now the site of new housing. Mobile produce vans also served the community, delivering bread, meat, fruit and vegetables, as well as ice cream sold by the DiNardo family.

Ref: Old Gartcosh Post Office, at the bottom of Lochend Road, now replaced by new housing. Photo taken from Gartcosh Local History Group.

https://sites.google.com/site/gartcoshlocalhistory/in-around-gartcosh-places-sites-of-interest/the-old-schoolhouse/the-buildings-site

Leisure

Although Gartcosh didn’t have its own pub, the residents found plenty of other things to do with their leisure time.

In the early years of the 20th century, several organised sports clubs were established in the village, beginning with Mount Ellen Golf Club in 1904. With so many English residents in Gartcosh, cricket was a popular sport, and a cricket pitch was established in the 1920s, followed by the bowling club in 1926.

Ref: Gartcosh Cricket Team. Gartcosh Local History Group.

https://sites.google.com/site/gartcoshlocalhistory/in-around-gartcosh-sport-and-leisure/cricket

Although a cinema existed in nearby Glenboig, Gartcosh didn’t have its own cinema, but films were shown in Gartcosh Hall for a time.

In 1962, Gartcosh United Football Club was founded, and is now part of the Caledonian Amateur Football league. The club has developed many professional players over the decades, including Pat Nevin, Dave McPherson, and Derek Ferguson.

With several community groups established in Gartcosh by the 1960s, a decision was made to bring them together under the umbrella of the Gartcosh Works Social Club, along with the existing Works’ Club Association, which had provided a meeting place for employees of the steelworks.

The Works Social Club would provide a welcome leisure space, and the first licenced premises in Gartcosh. It served a community which was centred around the steelworks which by this time had become the dominant industry in the village.

It was this steelworks that would come to define modern day Gartcosh over the next two and a half decades.

Steelworks

The Smith & McLean works, which started life as Gartcosh’s first industry in 1865, had by the 1930s been taken over by the Colville family. Colville’s had opened their first iron and steelworks in Motherwell in 1872, and from small beginnings had come to dominate the industry in Scotland, representing more than 85% of the country’s iron and steel trade.

Ref: A group of women workers at the steelworks, date unknown but possibly during the Second World War. Image from East Dunbartonshire Archives

During the Second World War, with the men of Gartcosh away fighting, around 400 local women, many of them the wives and daughters of steelmen, stepped up to take on jobs at the steelworks. They were much in demand as crane drivers, mill operators, canteen and ambulance workers - and as helmet hands, making helmets for British and American troops from strip steel.

They also produced steel sheets for Anderson shelters and Nissen huts as the government issued them in their thousands to British householders. One female worker at Gartcosh remembered the job of painting Nissen hut sheets attracted a pay bonus, and a free pint of milk per shift, to counteract any possible effects from the lead poison in the paint.

Mary Lauchlan, one of the women called up to work at Gartcosh during the War, describes a typical week:

We wore navy blue boiler suits and worked a 5.5-day week of three shifts daily round the clock. Saturday was a half day, and we had Sunday off. I reckon we worked even harder than the men. Most of the women just hadn’t been used to hard work of that kind, but my goodness, how they stuck in.

Many women carried on working at the steelworks after the war, often as first aid attendants.

In the 1950s, shortages of strip steel and tin plate meant the government needed to hugely increase Britain’s capacity for producing steel. Having recently brought all steel companies under national control, they pumped money into the industry to expand existing works - and build new ones - to meet demand. Colville’s were given a £50 million loan to begin building Ravenscraig steelworks near Motherwell in 1954, which would go on to become one of the largest steelworks in western Europe. In the course of construction, the UK government returned the steel companies to private ownership in the hope they would make the industry more efficient and increase steel supplies even further.

By 1957 Ravenscraig was producing 400,000 tons of steel per year. Colville’s needed greater capacity to turn this raw material into cars, office furniture, refrigerators and washing machines, and so began expanding the existing works at Gartcosh.

Work began in 1959 to build a new sheet rolling mill at Gartcosh, on a huge 100-acre site which would dwarf the size of the original iron and steel works. The new mill represented investment of £14 million and would bring many more jobs to the area over the coming years.

Ref: Aerial photograph showing the scale of Gartcosh Steel Works. Canmore.

https://canmore.org.uk/site/68413/gartcosh-cold-rolled-steel-mill

In 1962 the steel industry was nationalised once more and the Ravenscraig and Gartcosh works came under the ownership of British Steel. The new Gartcosh mill began production in 1963 and was one of the best equipped plants of its kind in the world. It was closely linked to Ravenscraig, which supplied it with hot-rolled steel strip; this material went through five processes at Gartcosh, each taking place in a different part of the plant: pickling, cold reduction, annealing, tempering and finishing.

Andrew Watson lives in Glenboig but worked in the steelworks at Gartcosh. Interviewed in 2023, he described the dangerous, physical work involved in the industry:

I would be making an 80ft derrick [a type of crane] for a ship. The centre piece of the derrick is the diameter of that and it’s a circle. So, there was a big box unit in the factory about the size of that, this bit was open… So, you got the hand powered bogie, you’d to lift that up, catch it in another one, bring the two of them round and push it into this open bit. Meanwhile you’re round the other side, you’ve got the next piece, which is slightly a bit smaller, you put it in in your side… And there’s black sluggish stuff, you soak a cloth in it, put a match to it and then stand well away and you chuck it in and there’s a boof, that’s it burning! Then the next thing is you do is turn the air on, so you’ve changed the whole thing. Within five, ten minutes that piece of tube is white hot and you’ve got gloves to there [your elbows], your bare arms.

Just as the steelworks was gearing up production, Gartcosh lost its railway station as part of the infamous Beeching cuts. Now without a transport link, and with the community centred on the newly expanded steelworks, Gartcosh became a single-industry town.

Liz Ward moved to the village in the 1970s and recalls vividly her first impressions of a community in transition:

The original buildings from the [old iron] works were still just a shell, they were actually being demolished at the time. You could see that it had been a busy street, they came down and then there was absolutely nothing, nothing at all. And then eventually woods appeared, all these trees started to grow where there had been houses. There was no station, you could hear the trains going back over and kept thinking, oh it would be great if there was a station, we knew there had been a station at one time. And there was also a huge steelworks, smoke bellowed out all the time, which is the reason my house was black as coal at one side, it’s now no longer as black, thank goodness. But we could hear the workmen who went up and down the road, and horns from the works, so it was busy with workmen.

While the village of Gartcosh felt dominated by the massive steelworks, the works themselves would for the next two decades continue to produce thousands of tonnes of high-quality products.

But by the 1980s, the entire UK steel industry - still owned by the British government - would come under pressure as Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher made clear her intentions to sell it off.

British Steel was responsible for five major plants across Britain: Llanwern and Port Talbot in Wales, Scunthorpe and Teeside in England, and the combined works of Gartcosh and Ravenscraig in Scotland. It was thought that closing one steelworks would make British Steel more attractive to potential buyers. Rumours swirled that Ravenscraig was the most likely candidate, as it now needed its raw materials - iron ore and coal - to be shipped in from abroad. But it had already seen its workforce reduced and had adapted new working practices which meant it still consistently produced some of the best steel in the world.

At the time, a quarter of Ravenscraig’s output was sent to Gartcosh for processing, so it was suggested that closing Gartcosh would damage Ravenscraig’s economic case. Despite this, in August 1985 it was announced that Gartcosh was to close the following year, with the loss of around 700 jobs.

The decision was met with anger and disbelief by the Gartcosh workers, who faced few other job prospects in a community which was now wholly reliant on the industry. Fighting for their livelihoods, they organised a protest march to Downing Street, and set off from the gates of the steelworks on the freezing cold day of 3 January 1986.

Ref: The march to save Gartcosh Steelworks, 1986. Herald.

https://www.heraldscotland.com/life_style/14370141.thirty-years-closure-gartcosh/

The workers marched for 10 days to London, carrying a petition that had been signed by 20,000 supporters. The route took them past the former steelworks at Consett, Durham, which had closed just six years previously, and gave the workers a glimpse of their potential future if they did not manage to save their jobs. By the time they reached Downing Street, their protest march had become a national event, covered by newspapers, radio and TV stations across the UK, highlighting the plight of the steel industry and its workers.

Ultimately, the workers’ protests did not change the government’s decision, and Gartcosh steel mill closed its gates on 31 March 1986. It was another death knell for the steel industry in Britain. Ravenscraig held out for another six years before it too was closed in 1992, with the loss of another 770 jobs directly, and another 10,000 jobs linked to these in a community which, like Gartcosh, had depended on a single industry.

The main building at the Gartcosh steelworks was demolished in 1995, while the large galvanising plant building was used by a paper recycling company throughout the 1990s. After the company relocated in 2001, that building was also demolished.

Once a site of huge industry, the location of the former steelworks has undergone several phases of redevelopment to deal with contamination from its former use, including the removal of asbestos and hydrocarbon. The site is now occupied by Police Scotland’s flagship Scottish Crime Campus, opened in 2014 to bring together serious crime and counter-terrorism agencies.

Ref: Scottish Crime Campus. Building.

https://www.building.co.uk/focus/scottish-crime-campus/5063656.article

After the closure of the steelworks, the residents of Gartcosh, most of whom had either worked there themselves, or had family members employed at the works, had to find ways to rebuild their community and forge a new identity.

Gartcosh after the Steelworks

After losing its major employer, the population of Gartcosh stood at just 818. But the community would soon begin to grow again as the area became an attractive place for new housing developments.

Close transport links to Glasgow (the railway station was eventually reopened in 2005), an attractive and quiet semi-rural location, and initiatives from North Lanarkshire Council to develop ‘Community Growth Areas’, have seen thousands of new houses built at Gartcosh. By 2011 the community’s population had grown rapidly to more than 2,000 residents, and is estimated to be more than 3,000 today.

There have been new housing developments built by Oak NGate (Gartloch Avenue/Bishop Loch), Avant Homes (Johnston Loch) and Bellway Homes (Oakwood), bringing an influx of new residents and families to Gartcosh.

Liz Ward explains that for those who’ve lived in the community for a long time, the new housing brings both negatives and positives:

Well at first, I didn’t like the idea of them building [the new homes], and I don’t like taking away all the green space at all. But you know, It’s actually made it more vibrant, it’s actually quite good to have more children about. I mean I think there’s real positives as well. I don’t like the missing fields, and the fact that our wee geese and all that have disappeared down by the loch. But they’ve just moved down, further down to Duff’s farm, so it’s not as if they’ve gone completely, they’re not stupid these geese we’ve discovered! It is positive to have younger people. What is different is, saying hello to people, Gartcosh people are like ‘hello’, like that, everybody knew each other. Not now, that’s not the same… And you’ve got to make sure you lock your door and all that more and more. But that happens everywhere.

She also worries that so much new building is having the effect of erasing Gartcosh’s history:

Johnston House, which… was owned by the pub owners down there, then the Golf Club owned it, torn down for houses - wrong. The old farm building up there, okay, I know it was beginning to fall to bits - torn down. That was an old, old house too. We are losing all our old buildings. That’s an old building, 1913, the bit at the back is 1875, the same as the middle part in my house, I mean they should not be pulling down these buildings. The foundation stone is all set in that wall there, that says Gartcosh Public School, I think it says, 1875, they cannot get rid of these.

Recently, Gartcosh has seen other development projects focused on highlighting the area’s natural heritage. After decades of abandonment, the site of the original iron and steel works was found to be the home of the largest known population of great crested newts in Scotland - this protected species having made their home in an area once dominated by a noisy, dangerous and polluting industry.

A project to create Scotland’s largest urban nature park on the doorstep of Gartcosh was first mooted in 2013 and began to be developed in 2016. The Seven Lochs Wetland Park covers an area of 16 square kilometres and spans the Glasgow City Council and North Lanarkshire boundary. Taking in seven local lochs including Johnston Loch and Bishop Loch closest to Gartcosh, the park has created a network of paths, signage and community facilities, forging new connections between the communities on its fringes.

Johnston Loch. Image taken from Glasgow Live.

https://www.glasgowlive.co.uk/news/glasgow-news/scotlands-largest-urban-heritage-nature-11669977

A new road was built between Gartcosh and neighbouring Glenboig in 2018, bringing these communities close again since they last shared ties through the brickmaking industry more than a hundred years ago.

Today, with an ever-expanding population, Gartcosh is seeing further developments. Having been home to so few pupils just fifty years ago that they could all be photographed standing on the front step, 113-year-old Gartcosh Primary School is now severely over capacity. Plans have been proposed that will see a new community hub built at the north end of the village, encompassing a brand-new primary school.

And the village may soon see the return of industry, as plans were announced in late 2022 for a new whisky superfactory, to be built by Italian company Guala Closures on the site of the Gartcosh steel mill. Nearly 40 years on from the closure of the plant that to many will forever define Gartcosh, the community is marching on to a new future.