Glenboig

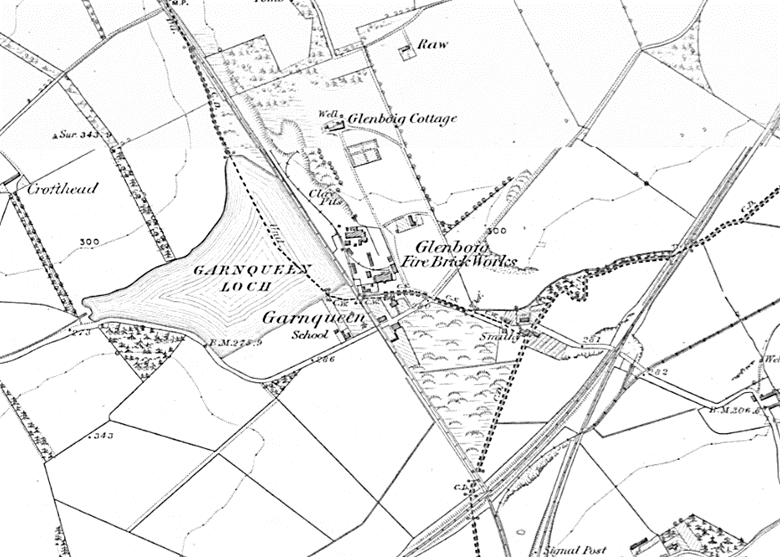

A community has existed in the area of modern day Glenboig for hundreds of years, but it was not commonly known by that name until more recent times. While a farm called Glenboig appears on maps as early as 1816, the area was more commonly known as Garnqueen, and Marnoch, before the coming of the brickworks which was to make the name Glenboig familiar not only locally, but eventually, across the world.

Ref: Glenboig Firebrick Works appears on the map (1840s - 1880s). National Library of Scotland.

Up until the early 19th century, the area not yet known as Glenboig had been a small farming community. But the place was to see its character change remarkably when fireclay works were established in the 1830s, bringing industry to the area. Over the coming decades, the fireclay industry would expand rapidly, and by 1895, the area was home to five separate works, and was the world’s largest producer of fireclay bricks. Glenboig village itself grew from a population of 120 in 1861 to house more than 3,000 people by 1939, all thanks to fireclay.

Fireclay and Brickworks

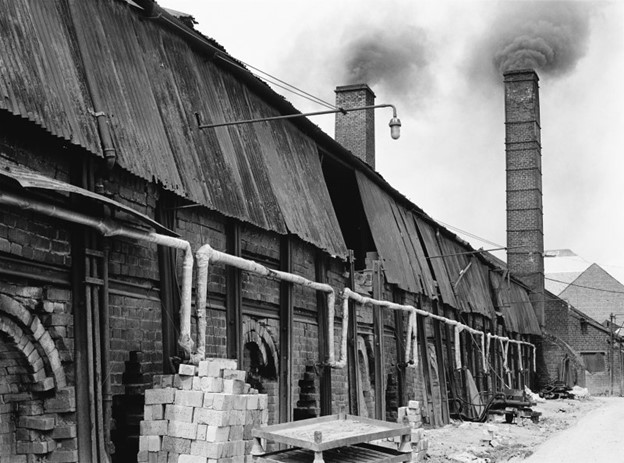

Ref: Workers at Hurll’s brickworks, Garnqueen, date unknown. East Dunbartonshire Archives.

Fireclay is a special type of hard-wearing clay which, when made into bricks and other products, can withstand very high temperatures. This made it perfect for use in the furnaces of the iron and steel industries which were at this time rapidly expanding in this part of Scotland. Glenboig and neighbouring communities were the perfect location for the fireclay industry, as a seam of fireclay, formed 300 million years ago in the carboniferous period, ran beneath the ground across large swathes of the area. As well as in Glenboig, fireclay works sprang up in nearby Heathfield, Garnkirk, and Cardowan, to exploit this rich natural resource.

Working conditions at the fireclay works were hard, with long days of backbreaking labour. Clay was dug from four mines around Glenboig, as well as other pits such as Glen Cryan at Cumbernauld. It was taken out of the ground as solid rock before being transported into a crusher which broke it up and ground it to a fine consistency.

The works produced many different sizes and shapes of bricks, which each had a different job to do, and the exact composition of clay for each brick had to be carefully formulated. A miller had the specialist job of making up the different clays which would be used for different bricks. These were formed using wooden moulds - at first this was done by hand, with brickworkers making hundreds of individual bricks every day. By the 20th century machines had taken on some of the work, but it was still a very physical job in noisy, messy and hot conditions.

Bob McMillan’s father worked in the Gartliston brickworks in Glenboig in the 1950s. He describes what a typical day was like for him:

We lived in Coatbridge and dad left for work at 5.30am six days a week, and after visiting the paper shop to collect papers for himself and other workers who did not pass a shop, he travelled by bus (Highland Omnibuses) to Glenboig. Here he left the bus at the railway bridge where the road divides to go straight on to Glenboig… From the main road it was about a mile of a walk along a blaes (burnt coal mining waste)-covered road to the brick works. Dad finished a very hard day’s work as a hand brick maker at 5.00pm and walked back to the bus. He would get home about 6.00pm covered in grey dust from the fire clay, often unable to straighten his back having spent a day bending down to punch holes in the semi-dried bricks laid out on the floor.

Another heritage project, ‘Glenboig Memories’, details the words of John Hamill, who also worked at the brickworks in the 1950s and describes the dangerous conditions workers endured (Ref: https://sites.google.com/site/glenboigmemories/people/john-hammil):

We were the Burnt Squad, working with brick already fired, timmin' the kilns. Sometimes the specials had to be fetched out of the kiln for an order and we would have to go in with a wet sack over our head and body for protection from the heat. We wore hand guards made out of tyre rubber but sometimes the heat went right through and you couldn't hold a cup of tea. The temperatures in the kilns reached 900 - 1,000 degrees, and they were cooled by massive fans. Then a brand-new type of kiln was introduced, a tunnel kiln, and the green [unfired] brick was loaded onto train wagons which ran on tracks round and round the tunnel getting hotter and hotter. We had to hand pack them straight off the 'caurs'. Each wagon held between 7.5 and 9 tons of brick. There were three of us working and we had to shift 50 tons each every day. That was increased to 60 and 65 tons after I had left the brickworks. We worked in wooden clogs. The heat from the bricks had the soles off your boots in a week.

Ref: Gartliston Brickworks, Glenboig. Image from Records of the Scottish Industrial Archaeology Surve, University of Strathclyde.

https://canmore.org.uk/site/45766/glenboig-gartliston-fireclay-works

The brickworks dominated the village, and most men in Glenboig worked there. Job opportunities for women were few, so if they couldn’t get work as a shop assistant or as a maid for a wealthy family (there being not many in the area), they often ended up working at the brickworks alongside the men. John Campbell remembers:

My mother worked in the brickwork, maybe packing the bricks or packing the kilns. A lot of women laboured, they helped to make the bricks and carry them and they worked at the machinery, packing the wagons and unpacking the kilns. That was the only work there would be for women, working in the brickworks…

Ref: Female employees at the Star Works, Glenboig, around 1912. Image printed in The Raddle, vol. 2.

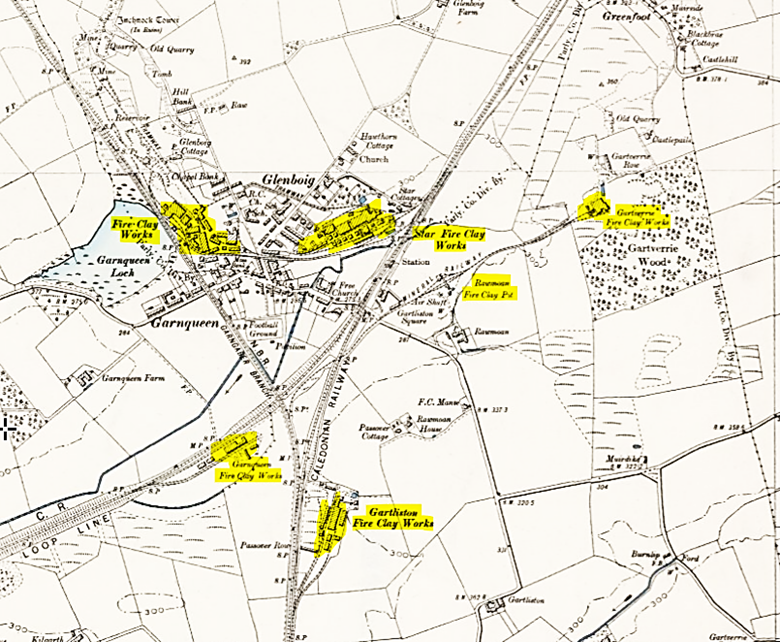

During the late 19th and early 20th century, brickmaking dominated life and work in Glenboig. Between the 1830s and 1895, five separate fireclay works were opened in the area. They were operated by two main companies: the Glenboig Union Fireclay Company (itself a merger of two former rival companies), which operated the Old Works and Star Works next to Garnqueen Loch, as well as later, the Gartverrie works east of Glenboig; and P&M Hurll, whose founders had split off from the Glenboig Union Fireclay Company to set up their own works, Garnqueen and Gartliston, either side of the Monkland & Kirkintilloch Railway.

Ref: A map from c.1913 showing the five fireclay works, plus Ramoan Fire Clay Pit, highlighted in yellow.

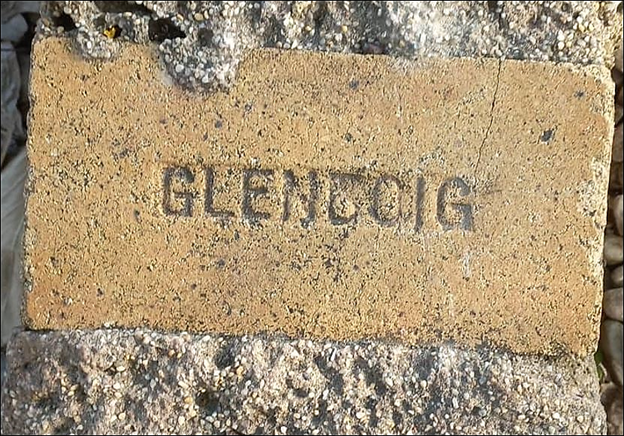

Glenboig became a centre for brickmaking and soon its products were renowned across the world for their quality - winning awards of merit, being showcased at international trade exhibitions, and used in industry everywhere from Russia to Australia, Canada and the USA. Such was the association of the name “Glenboig” with quality firebricks that in 1883 one of the Glenboig brickmaking companies took another to court over the rights to stamp the name into their bricks.

After a successful start, the industry began to wane in the 1920s as, despite record profits, the companies failed to invest in new technologies to make them competitive. The works saw an increase in production again during the Second World War as demand again increased from iron and steelworks manufacturing tanks and weapons. The Glenboig Union Fireclay Company was, in the 1950s, producing more than ever, turning out 200,000 tonnes of firebrick every year.

Ref: A Glenboig brick found on Flower Pot Beach, Trinidad. Photo taken from Scottish Brick History.

https://www.scottishbrickhistory.co.uk/glenboig-brick-found-in-trinidad/

But fortunes were to change once more. As heavy industry developed in other parts of the world, and British products became less competitive, brickmaking - like so many other industries in Scotland - began to come to an end. By 1958 the original Old Works had closed. P&M Hurll stopped operating at Garnqueen and Gartliston around 1962, while the Star Works stayed on until 1976, when it too closed.

Not much remains of this once-thriving industry in modern day Glenboig, but the community is still rightfully proud of its brickmaking heritage. Bricks bearing the various stamps of the works around Glenboig are still unearthed today in places as far afield as Ukraine, Alaska, Australia, Trinidad and Brazil.

Life in an Industrial Village

The work of mining and brickmaking was hard, and the living conditions in Glenboig at the time of all this industrial activity were equally difficult.

The opening of the fireclay works brought workers to Glenboig to settle, many of whom were Irish immigrants, as well as Poles and Lithuanians. To house these new workers, the fireclay companies built workers’ cottages - ‘single-ends’ with one room and a built-in bed. There was no room to spare - so much so that when someone died, their coffin had to be kept in the bed until the day of the funeral, when it was taken out of the house through the window, as it was impossible to remove horizontally any other way. While giving workers and their families a roof over their heads, the cottages were owned by the fireclay works, so if you lost your job - or went on strike - you also lost your house.

Once such strike took place around 1901, when Glenboig Union Fireclay Company was making record profits of £16,000 (around £2 million in today’s money). Frustrated at the dangerous, difficult conditions and their continual poor pay, the workers went on strike. Garnqueen Square, where the Glenboig Life Centre now stands, was where the brick workers’ cottages stood, and it became the scene of forced evictions in retaliation for the strike, with eight families turfed out of their homes, including the secretary of the local miners’ union.

Garnqueen Square was, a few years later, also the scene of an incident which highlighted both the danger of the working conditions and of the densely packed housing. A Polish miner, Paltrus Vikiatus (also known as Peter Wolff, as it was common at the time for immigrants to change their names) had taken in a lodger, another a Polish miner. It was winter, and the lodger had a block of gelignite which had frozen solid, which he decided to place on the hob to thaw out before his night shift. In the heat from the fire, the gelignite - predictably - exploded, with tragic consequences. Four people were killed, including two of Paltrus Vikiatus’s children, and another eight injured.

Ref: The aftermath of the explosion in Garnqueen Square, February 1910. North Lanarkshire Council.

https://www.culturenlmuseums.co.uk/SIModes/Detail/26489

John Campbell grew up in Glenboig in the 1920s, and although he enjoyed his childhood living and playing in an industrial village, he looked back on life there through different eyes as an adult:

Glenboig, it was a great place to grow up, from a boy’s point of view looking back on it. But it was a horrible place really, there were no paved roads, the only paved road was the main one going through, but all the other ones were just hard ash from the furnaces, and there were the clay mines, the ones that were working and the ones that had been abandoned, there was the brickworks, the hutch line, the railway, I mean… But there was no real danger, you learned to live with it you know? It was great… looking back on it. There were hazards, there was a big fence that led into the brickwork which was all barbed wire. I remember climbing up on it and my foot slipped and my hand, I’ve still got the scar there yet, the barbed wire caught me and I was left hanging. They had to go for my mother to come and lift me off. I remember my finger hanging out. There was also a wee boy killed at the level crossing, with the gates.”

The brickworks were still a predominant part of life for those that grew up in Glenboig later. Teresa Watson was born in Glenboig in 1945. She remembers:

When I was in primary school, we walked down the hill and there was a railway crossing there and that was the wee train that came from the brickwork, and if you were lucky, you got through before the train came. But I remember too, you know, the hooter would go for the end of them, at lunch or whatever, there was a swarm of men coming out, hundreds and hundreds and hundreds. If you were a wee girl you know, ‘what’s this all about?’, I remember. I also remember they put the bricks on the lorries and they’d trundle up through Ramoan, and you could feel the vibration on the clay, you know the coal mine and the clay mine, we were on the clay up there, you could feel the vibration.

Alongside the brickworks, Bedlay colliery had opened near Annathill to the north of Glenboig in 1905 and provided another source of employment for men in the surrounding area. At its peak in the 1960s up to 1,000 men worked there. Like brickworking, it was hard and dangerous employment, and the threat of accident and injury was never far away for families of those who worked in either industry.

Teresa Keating was born in Glenboig in 1947, and remembers an incident from her teenage years:

There was a mining disaster… all I can remember is people running through the village, saying that something had happened at the pit. And there had been a collapse, and they put out - bear in mind that I’m a teenager at this time... My eldest brother was in the pit. And the chaos in the village, because nobody knew, at first it was, there had been a disaster. They weren’t even sure what pit it was in. The media didn’t keep up the way it does nowadays. And I can remember the melee and people in the streets that day, and we didn’t really know until later on in the day what pit it had been, how many deaths there had been, how they got the survivors. We didn’t know that until it was dark, it was the evening. And that was traumatic, that stayed with us for a long, long time.

Leisure

Despite the dangers associated with living in an industrial village, Glenboig was a hard-working community that still found time for leisure and social life.

Ref: Brickworkers and families on an outing from Glenboig, date unknown. East Dunbartonshire Archives.

As well as providing housing, the brickwork companies had also built the Gartsherrie Institute, where Glenboig residents would meet for events, dances and enjoy a bit of competitive sport. John Campbell remembers:

It was a building in the village, it was built and run and organised by the brickworks company. There was always a penny or tuppence off everybody’s wages to go towards the Institute, its upkeep. They played billiards and a game called Summer Ice. Summer Ice was a long narrow table with little round metal discs, very shiny on the bottom. They polished the long board with floor wax or something, the kind of stuff they use for floors for dances, and there were rings, three rings, and you got into the centre and knocked the other man’s discs out. That was a great game in these days.

Ref: Glenboig Institute, date unknown. East Dunbartonshire Archives

For children, entertainment was simple - playing handball against the gable ends of the cottages, games of football, or swimming in Johnston Loch.

More excitement was to be had when the travelling shows would come to town. The Codona family were regular visitors to Glenboig and would set up their showground at Carrick Place. Willie MacDonald, writing about his days growing up in Glenboig in the 1920s, remembers the sights - and smells:

The main attraction was the big boat which was set in motion by two young strong local men pulling together on a rope. The bigger the thrill you wanted, the nearer the extreme ends of the boat you would go to get the most height. There was a big tent called a geggie in which the show people would put on plays and they would be the actors. We would catch on to particular parts of the plays and would act them weeks after the shows left, trying to impersonate the poor actors. The admission to the geggie was one penny. A man would walk about the village, to create interest, on high stilts. A strong man would hold two horses pulling at either side of him until a rope would break. He would also hold a big stone on his head and invite the men to break it with a hammer. In the evening, everything would be in full swing with smelly paraffin lamps supplying the light.

Glenboig had a cricket club who played at Inchneuk Farm, as well as two football teams. John Harold grew up in Glenboig in the 1930s and 40s and remembers:

There was two football teams, one of them, the park is still there. St Josephs, it was St Joe’s, which was across from the cinema, it’s still there, it still uses the football park. And the other one was further up in the village, just up the road there. Carrick Park, that was the Glenboig Juniors. Joe’s were an amateur team, Glenboig Juniors I think were semi-professional - I mean it was probably a pound a week or something like that.

As John mentions, the village also at one time had a cinema. Teresa Keating explains the building still stands today, although now it is a vehicle refurbishment and repair centre:

The old building is still there, if you stand back and look at the face shell of it, you’ll see where the steps are and how, you know the white doors that they had. And I can remember the wee door inside, where you got the tickets to go in and that. There was always an A movie and a B movie you know, so you got your money’s worth. When we were little it kinda closed until we were maybe into our later teens you know, but when we were at kinda primary school or that, you used to get money back on ginger bottles and things like that you know. So, we would do that and get money back for the cinema on a Saturday and then when you were a wee bit older… they had a balcony. You could go up to the balcony or you could sit at the back you know.

John Harold has similarly fond memories of the cinema:

Films changed four times a week, you had Monday and Tuesday, and then it changed on a Wednesday, then Thursday and Friday, they were all double bills. And a Saturday was different, there was a matinee on a Saturday with the kids and then there were two shows in the evening.

Ref: Glenboig’s former cinema, pictured after it closed in 1985. East Dunbartonshire Archives.

In more recent times, Glenboig St Joseph’s was known as one of the best badminton clubs in Scotland, and created many national-level players. Glenboig United Football Club was founded in 1986 and continues to provide coaching and competition for players as young as four.

Also set up in the 1980s, Joe’s Fun Club was founded by Teresa Keating, who worked as a teacher, with one of her colleagues. The club provided activities for children with additional support needs, for whom there wasn’t local provision in Glenboig. She explains:

There was another teacher in the village and myself, and we were aware of the lack of amenities for special needs people. So, we started a club for them, we decided we would pilot it and see how it would go. We publicised it and we looked for members and we realised it wasn’t just people in Glenboig, there was people further afield, Townhead, Annathill, Moodiesburn… So, within a short space of time, we had quite a register.

"The first member we had was a laddie called Joseph, now I knew Joseph from when he was a wee tot… Joseph was born with multiple problems, he was mobile but he had curvature of the spine and communication problems and all the rest of it. So, he was the first one in our register and we decided to call the club after him. Joe’s Fun Club. And within a short space of time Joe’s Fun Club became an entity in itself and we had terrific carers and minders and I was the secretary of it. [My husband] Henry used to do the West Highland Way, well I’ve done it lots of times myself. And he started to do it as a sponsored thing and he would take some of the teenagers that were carers, you know that looked after then our clients. He’d take them away to do the West Highland Way and they would all get sponsorship and that’s how we started to raise funds, because funds were low on the ground in those days. That was… that went on for years, we had dinners out and we had residentials and all the rest of it. And it was great days, great days.

School

Being for many years a sleepy rural village, Glenboig didn’t have a dedicated school until 1875. Up until then, classes had been held in the church, masonic hall and the Gartsherrie Institute. The rapid influx of workers to the newly opened brickworks around the 1860s meant more children were now living in Glenboig, and so a dedicated school was built.

The first school building didn’t last long, becoming victim to the subsidence caused by the heavy mining of the area. It was abandoned in the early 1900s and temporary classes took place in wooden huts until a new school was built in Ramoan in 1928.

Another school, St Joseph’s, was opened in Glenboig in 1881, but this too needed to be replaced as a growing population created the need for more places. In 1927 a new St Joseph’s was built which took in the site of the first school and the church next door.

John Harold remembers his school days in Glenboig during the Second World War:

So we started there, and every morning was the same, we lined up in the corridor and Miss Glennan would come round, she would make sure that you had your gas mask, she’d look at your hands and make sure that your nails were clean, check your shoes to see that they were clean… some of them didn’t have shoes.

"Miss Donnelly, she was the primary teacher, first primary. The room had a fireplace in it and the janitor had to come in every now and again and chop up the coal, you know. I think the other ones had radiators. There was Mrs Egan, Mrs Shoan, that’s the one I finished up with. They were all “Mrs”, although I think some of them were married, at that time if you married you lost your job, although I think maybe during the war then that changed.

Ref: Glenboig Public School, 1926 - class took place in temporary wooden huts until the new school was built two years later. ‘Glenboig Memories’.

https://web.archive.org/web/20201030104401/https://sites.google.com/site/glenboigmemories/people/john-campbell

Now, Glenboig Primary and Our Lady and St Joseph’s primary schools share a campus, opened in 2008, while secondary school students’ nearest high school is in Coatbridge.

Shops

Glenboig at one time was home to a number of small shops serving the community. John Harold remembers:

There was a Post Office, run by Mrs Watson who lived in the same block as us at home. She was there until she was 100, she was still working - I say she was working, her daughter was doing all the thingmy… Next door to her was her husband who had a shop that sold radios and people used to come, mostly from Annathill with their batteries or accumulators to get them charged up because they had no electricity up there.

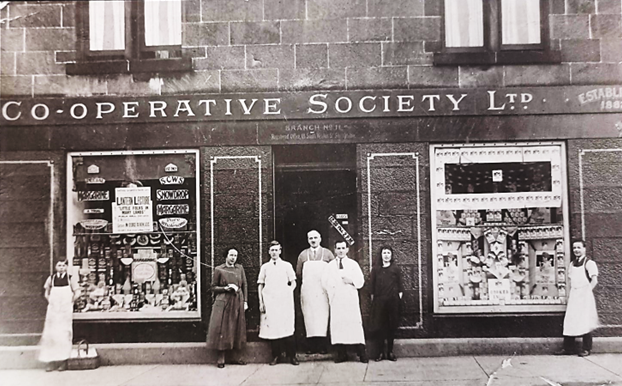

"Then there was a joke shop, well he didn’t know at the time, but they said joke paper shop, then there was DiNardo’s, DiNardo’s was a café, you couldn’t sit in it, it was just an ice cream... then there was Chapman’s the butchers next to that. Then there was the Co-operative, it had three sections, although it was the one building, you got three sections, first section was…the fleshing department, then there was the grocer’s and then the next one was the drapery.

The Co-operative at this time operated on a dividend model, known as the ‘Divi’, where shoppers who had signed up as members were paid a share of the shop’s profits back, according to how much they spent there. Some branches offered a higher rate than others, as Teresa Watson recalls:

As a child I used to go on the bus, Carmichaels bus, and we would go to Mollinsburn [three miles from Glenboig] because the Mollinsburn was part of Kilsyth Co-Operative and the Dividend was more… I’d go there with my mother and you just had an hour before the bus would come back. The bus dropped you at Mollinsburn and then it would went to Kilsyth and came back. So, you had an hour to get in and out the shop. So my mother used to send me in with the store book, you had your book, run in first and you put your book on the pile and then you sat and waited until they call your name, and I remember it was you got butter and fats, cut it off, big lumps of cheese and then you’d rush back and stand and wait for the bus, and if you missed it you’d an hour.

Ref: Muirhead Co-op, 1926. East Dunbartonshire Archives.

Railway

Glenboig village was lent a unique character by having not one but two major railway lines running through it. These were two of the first railway lines to be built in Scotland (and therefore the world). The Monkland and Kirkintilloch Railway was opened in 1826 and ran through the centre of Glenboig along the edge of Garnqueen Loch and next to the fireclay works. It connected the coal fields of the Monklands to the city of Glasgow by joining up with the canal at Kirkintilloch. A few years later, in 1831, the Glasgow and Garnkirk line opened, running on the other side of Glenboig.

Sitting on top of two major transport links meant Glenboig’s fireclay and brickmaking industries had ready access to markets and materials, which helped assure their success. The railways also lent a unique character to the village, in which it was impossible to enter or leave the Main Street without going over or under a railway.

For a hundred years, these two railway lines meant Glenboig sat at the centre of busy transportation routes for coal, materials, freight and passengers. By the start of the 20th century, the Monkland and Kirkintilloch railway line would see a gradual decline, having been taken over by other methods of transporting coal and freight. After the closure of the fireclay works the railway was redundant, and the line through Glenboig eventually closed completely in the 1980s. Today, walkers can still follow the line of the Monkland and Kirkintilloch railway along the path through Glenboig Village Park at the side of Garnqueen Loch, north past the site of Inchneuk Tower and up to Drumcavel Road.

The former Glasgow and Garnkirk line would experience a different fate, as it remained a popular route for passenger travel. While the line still exists today, running from Glasgow through Gartcosh to Cumbernauld, a station that had opened at Glenboig in 1879 and served the community for 77 years was sadly closed in 1956.

Glenboig Community Today

As with many post-industrial communities in Scotland, Glenboig suffered its share of problems in the 1980s and 90s as employment opportunities and investment decreased rapidly. The last brickworks had closed in 1976 and Bedlay colliery would follow in 1982, leaving Glenboig without an industry for the first time in 150 years.

This decline led to an increase in drug and alcohol misuse, bringing with it its own problems. But Teresa Keating explains how an intervention brought about by a small government investment around the year 2000 set the community on the right path again:

Drugs were rife all over different parts of Scotland… and the Scottish Government stepped in, and they wanted to try and alleviate some of the problems in Scotland. And through the council there was the princely fund of £11,000 allocated to Glenboig to see if it could make any kind of dent in the drug situation. The police called together all the active groups. Basically, what they wanted to see if anyone was willing to get youth work training. Well, it was a given, Teresa [Aitken] was already working with the youth, I was working in other ways, I was working in education. We had families of our own. We signed up for it, there was quite a few folk that signed on, but eventually we were left with maybe five or six of us that actually went for that training. Henry, my husband, came along as well, he was there.

Around the same time, North Lanarkshire Council announced they intended to close the Neighbourhood House, the last main public building left in Glenboig. The two Teresas, Keating and Aitken, put their training to good use and alongside the community, decided to fight the closure. They set up the Glenboig Neighbourhood House organisation, which would eventually become the Glenboig Community Development Trust.

Teresa Keating explains how it all started:

We started doing the Neighbourhood House, which was an old Social Work building, we kind of adapted what we could to suit ourselves. The youth work was growing and growing and then we started the girls’ group. The next thing that we started to target was the village Autumn Group [a reminiscence group]. Asking older folk to bring pictures along with memories.

Before long, the new activities led by local volunteers took on a life of their own, and the Development Trust began to employ paid staff. This led to the development of the Glenboig Life Centre, another property to be taken into local community control when the council was no longer willing to maintain it:

We were offered this building [the Glenboig Life Centre] but we had to have 53 car parking spaces. Now there’s nowhere even that North Lanarkshire [Council] has 53 car parking spaces. So, we thought that’s not going to work. The Empowerment Bill came out where they [the council] were wanting to sell off some of the community centres because they couldn’t upkeep them any longer. They weren’t getting used properly and all the rest of it. That’s when we moved in.

Ref: Glenboig Life Centre. Photo by architects Fleming Build.

https://www.flemingbuild.com/project/glenboig-life-centre/

The Life Centre has since gone from strength to strength, becoming a thriving community venue at the heart of the village:

The Post Office was going to be moved out of Glenboig, they were closing it, the one which is a hairdresser’s and beautician’s now. So, Teresa [Aitken] and the rest of us got together… We thought right, you can’t let them close the Post Office, you need a Post Office in a village. So, we got in touch with Post Office counters, and they told us, right, they’d need to have a couple of people responsible for it and they would need to be interviewed and do a presentation… So, Teresa and I was hit for that! Never thought I was going to be interviewed again in my life. So anyhow, we went and we were successful and we got the Post Office licence and that’s when we came into this building and that. And we came in, and down at the front, which is the entrance now, there was a wee kitchen there, but it wasn’t big enough. We opened up as a café but it really wasn’t big enough. And then as I said we grew arms and legs and eventually we wanted to buy here. And we were successful, we got money from the Scottish Land Fund, North Lanarkshire and their generosity took over £40,000 for it. We got it and we got this place and then we asked the community what they wanted, you know.

Around the same time the Glenboig Development Trust was working to rejuvenate the community, locals in Glenboig set their sights on another development project.

Having been the site of the once dominant Glenboig Brickworks, a now-vacant piece of land next to Garnqueen Loch was in need of regeneration. In 1999, residents got together to discuss problems affecting their local environment, and as a result decided to develop Glenboig Village Park on the site.

The group identified the loch as a focal point of the village and saw the development of the park around the loch as an opportunity to foster the community’s appreciation and enjoyment of their natural environment.

A committee of residents engaged with local partners and successfully applied for more than £440,000 to make the park a reality. Work began in January 2002 and the park was officially opened in summer 2004.

Ref: Garnqueen Loch, part of Glenboig Village Park. Seven Lochs Wetland Park.

https://www.sevenlochs.org/22263

Alongside the rejuvenation of the community, Glenboig has seen the growth of a number of new housing developments, bringing new people in to the area. The village now once again has a population in the thousands, just as it did when it was a thriving brickmaking and mining area. While the industry no longer remains, Glenboig continues to work hard to maintain its heritage and build a strong community.