Ruchazie

Early Days

The lands on which modern-day Ruchazie now sit were once part of a large country estate owned by the Hamilton of Silverhill family (who also owned nearby Provan Hall).

Robert Hamilton of Silverhill sold the land to the City of Glasgow in 1667, and by the 1730s it had been portioned out into farms and became home to a small crofting and farming community. The clay soil of the area, as opposed to the stonier and sandier soils to the north and south, made the land around Ruchazie some of the best in the district for farming.

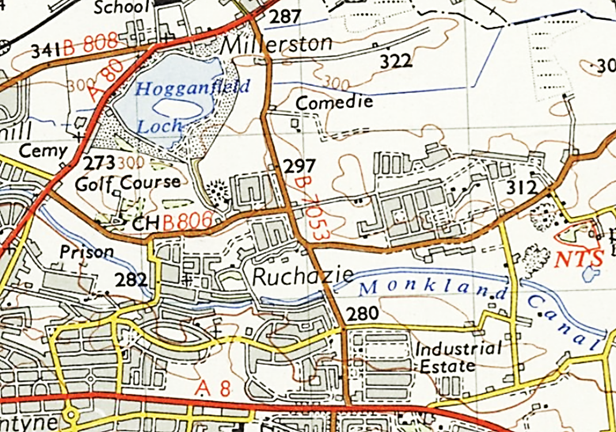

Ref: Map from the 1750s showing ‘Rachezie’ in the centre with Hogganfield Loch to the northwest. The parallel hatched lines all around indicate ploughed farmland.

Ruchazie formed part of an area known as the Provan. The name Provan came from “prebend” which was a name given to a district from which a clergyman of the church made an income. The Prebend of Barlanark covered a large area to the northeast of Glasgow that encompassed Ruchazie, Queenslie, Barlinnnie, Blochairn, Hogganfield, Milton, Riddrie, Craigend, Garthamlock and Cardowan. Over time it became known just as the Prebend, then Proband and finally Provan. Ruchazie is thought to be one of the principal settlements in the whole of the Provan area, and is often one of the few named places on maps of the area from the 1700s, indicating its importance.

The name itself was spelled in a variety of ways before settling on “Ruchazie”, including Rachasie, Rachesie, Rachaisie, Rachazzie and Roughazie. It is thought to come from “ra” or “rath” (pronounced raw) meaning a fort, and “ea” or “esc”, meaning water. Thus, Ruchazie is “a fort beside the water” (the water presumably being Hogganfield Loch).

Ruchazie was also known locally for another reason. A school, one of the very first in the area, was founded there in the late 17th century. It would have been established around the time of the Education Act of 1696, which aimed to provide education for the masses and ordered locally funded, Church-supervised schools to be established in every parish in Scotland. This meant poorer families now had the opportunity to give their children an education, and would lead to Scotland having a reputation as the best educated country in Europe at the time.

Ref: Old Ruchazie school house

The school at Ruchazie was built from funds donated by local crofters and tenants from their own money, eager to give their children an education. It would have been a basic building, likely made from wood with a thatched roof, but attracted pupils from all over the Provan area.

By 1739 a new, brick school was built just off Gartloch Road. Classes were taught in English, Latin, writing and arithmetic. Parents still had to pay for their children to attend - in the 1800s this was 12 shillings a year (around £30 in today’s money), however poorer families qualified for the discounted rate of eight shillings. The school remained the centre of the village at Ruchazie until the 1880s when a new school was built at Garthamlock, and the schoolmaster transferred there.

Industry

While Ruchazie itself remained a sleepy hamlet surrounded by farms, industry was not far away. The Monklands Canal was built in the 1770s to make it easier to transport coal from the collieries of the Monklands into the city of Glasgow. The route of the canal passed just half a mile to the south of Ruchazie School. The canal would much later, in the 1970s, be paved over to make the new M8 motorway, which created a new hard boundary that would come to define the southern edge of Ruchazie.

The area was also home to the Gartcraig Colliery, which mined coal and fireclay from 1870 to 1918. The pit fed the nearby Gartcraig fireclay works, which like others in the area such as at Cardowan and Glenboig, made hard-wearing bricks and other products from the clay.

The 1920 and 1930s

Ref: Mrs Helen Murphy with daughters Mary and Isobelle at the Sugarolly Mountains, 1962. Photo: Cranhill Arts Project.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/glasgowfamilyalbum/5430438627/in/photostream/

In the early years of the twentieth century, Ruchazie remained a quiet place, its proximity to Glasgow and lack of its own industry leading some to think it had been left behind in the march of progress. A local resident writing in the 1970s remembers the village of their youth in the 1920s:

There was a farmhouse [which was still standing in the 1970s], two or three thatched cottages, a blacksmith shop, a general store and a little school house for about half a dozen children. This comprised Ruchazie village.

The young people of those days knew it as a spot for picnics and walks, which was not too far away from the city. You could walk from Shettleston through country lanes up the ‘Sugar-olly Mountains’ [so called as they were made from dark brown sludge dredged from the canal - which was the colour of liquorice], over the canal bridge which was then the “tow row” bridge, to Hogganfield. At one side of the bridge there was a four-storey tenement building which used to house farm labourers and the men who sailed the barges which carried goods from Gartsherrie to Port Dundas.

In the 1920s, the Corporation of Glasgow (a precursor to Glasgow City Council) drew up plans to build a major suburban park area next to Hogganfield Loch. While a smaller park was eventually developed around the loch, the area encompassing Ruchazie was not included. But the Corporation would soon draw up other schemes for the area that would have a dramatic impact on this sleepy village.

From Village to Housing Scheme

In the 1930s, Glasgow had a housing problem on its hands. Many of the tenement homes built in the 19th century were falling into disrepair, and inner-city communities were overcrowded, unsafe and unhealthy places to live. A housing survey of 1935 found some areas of Glasgow to have rates of overcrowding as high as 35% - this compared to an average of just 4% in England. It seemed the lands around the tiny hamlet of Ruchazie were a prime candidate for development.

Plans were interrupted by the Second World War, but by its end, Glasgow’s housing problem was worse than ever. With the 1949 Housing Act, the UK Government set aside large grants to local councils with the specific aim of encouraging large scale housing projects.

In the 1950s, new schemes were already in development at Easterhouse to the east of Ruchazie, and Cranhill to the south. Glasgow Corporation decided to develop a smaller scheme in between.

More than 1,500 homes were built in Ruchazie in just a few years - some individual houses, but most small ‘cottage’ type blocks of flats. The design of the houses was a vast improvement on the Victorian tenements that those moving from Glasgow had just left. The veranda entrance design seen widely in Ruchazie was much used in housing developments of the period, and at the time won the Saltire Society’s award for the best designed flats in Scotland.

Ref: Frances, Mary and Nan Scott, Balcomie Street, Ruchazie 1956. Photo: Cranhill Arts Project.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/glasgowfamilyalbum/4473715951/

Though undoubtedly an improvement on previous conditions, the rushed construction of the new flats meant that many later suffered problems, including damp. Little attention was paid to landscaping or environment, and few amenities like shops, pubs or leisure facilities were built among the thousands of new houses that had been built so quickly.

A map from the 1950s shows a far more built-up Ruchazie, but before the coming of the M8 motorway (which follows the line of the Monkland Canal). The motorway has created a more definitive boundary between Ruchazie to the north and Cranhill to the south.

While Ruchazie later suffered the same deterioration seen in other schemes hastily erected in the 1950s and 60s, those living there at the time remember a close-knit and proud community.

Mary Sinclair-Ferguson, born in Ruchazie in 1957, describes what it was like growing up there:

We grew up in a tenement building, we lived in the lower ground flat and so my mum and dad shared a room with my brother, my sister and I shared a room with my gran, there was only two rooms in the house. We had a coal fire in the sitting room, we had a coal fire in the bedroom. We had an inside toilet which was good. We had the kitchen and a hallway. We had a front garden.

It was very friendly, like all the mums and all that always came outside with the kids and played games and stuff like that. There were rough bits of the scheme but our bit was pretty good. We had a good swing park so we were there most of the time when we were young. The park-keeper made sure we weren’t in there after hours.

Even if we drew [with chalk] on the road or the pavements or the closes where we stayed, we had to wash it off. I think our parents kept the place really good, like the gardens round there were a lot nicer than what I would say even now. You know everybody really looked after the place. Looked after each other, I think that was the real good thing about Ruchazie.

Grace Wright moved to Ruchazie in 1967. Despite the lack of facilities for children, she likewise remembers a close-knit community where young people made their own entertainment:

We never really had a park, our park was Hogganfield Loch, so we never had a park with swings and things like that, so we just made our own entertainment.

“Everybody in the close all knew everybody and all the parents looked out for everybody’s children. So, like school holidays, like my grandmother and father had to work, there was lots of kids up the close, so we just all went to the loch every day and we used to take our jam sandwiches and our diluting juice and that was it every single day in the summer holidays. And we just all looked after each other. And then into the summer we done the rhubarb picking at Hogganfield Loch as well so I think we got like half a crown or something a week, so that was us, we were really wealthy!”

“All the kids we all just stayed together, played together, none of us ever wandered away or anything. We made our own entertainment, jumping the midgies and jumping the fences - you name it, we done it. We used to take a walk up to Wallace’s… I’m trying to think now, Wallace’s Well. It was up past Hogganfield Loch… We used to go walks up there, we used to take walks down to Alexandra Park, and then there was a farm at the bottom of the road that the boys up the stairs, his grandmother used to work in it, so we used to go down there a lot, especially when the wee baby chickens came in. Willie’s Farm, and they used to take dogs in, boarding, for people to go on holiday.

School

Such was the speed that new houses were built in the early development of Ruchazie, and new families moved in, that many were living there before the community had its own school. One resident who moved to Ruchazie in 1953 remembers attending Riddie Primary, a mile away. Their route to school would take them past fields where inmates from nearby Barlinnie prison could be seen working each morning.

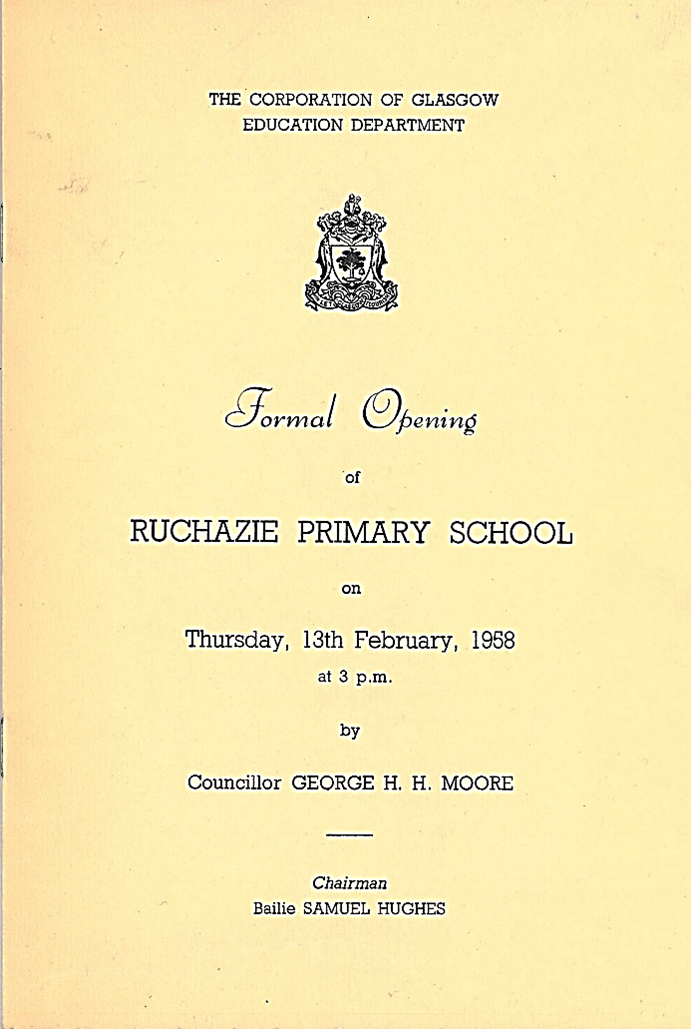

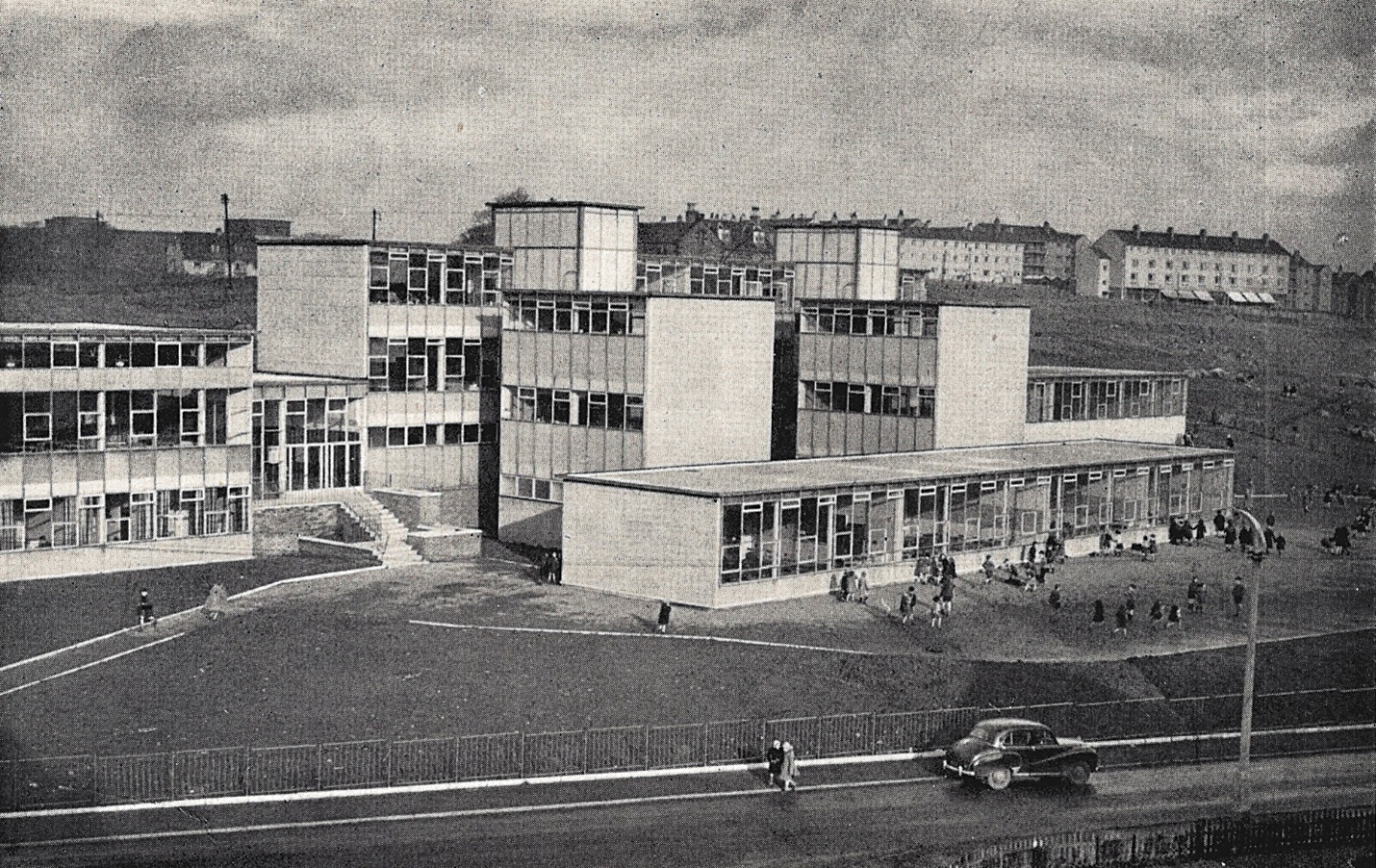

It would be the late 1950s before Ruchazie had its own schools, with St Philip’s Catholic Primary School opening in 1957 and Ruchazie Primary next door in 1958. Mary Sinclair-Ferguson attended Ruchazie Primary and remembers:

I had a teacher called Mr. Scott, and right to this day the kids laugh because when the French national anthem comes on, I know it all, cause he used to make us sing it every morning. And then we had another teacher, Miss Burns she used to live just on Ruchazie Road, she used to, when the girls were naughty in there, take their skirt up and skelp them round the backside.

Grace Wright also attended the school but didn’t enjoy her time there. Being of Italian background, she experienced discrimination from the other children:

My grandparents adopted me so I was living with them, in Blairlogie Street, we moved from Balornock, why I’m not 100% sure but, we moved anyway. I started school here in the primary school, Ruchazie Primary School. Which I hated. They called me Paki, cause I’ve got dark skin, I was a lot darker when I was younger, and I looked Asian because I had long pleated hair and I was really dark when I was young, I’m Italian so… they had never seen anybody with any other colour of skin other than really white, so it was, I suppose it wasn’t quite normal for them to see somebody a different colour, you know, and for them to have that reaction.

John Duffy’s dad was the “janny” at St Philip’s in the 1960s and he attended the school when the family moved there from Garthamlock. He has a particularly fond memory of a visit from a certain caped crusader:

I loved St Phillips and especially in 1966, we actually got a visit from Adam West, who at the time was Batman. He was over in Scotland at that time doing a promotional safety, road safety things with all the kids. And he actually came, he drove into the school with his Batmobile. And you know, ‘Is that Batman?!’ And we loved it… I just wish I had a camera and I was a bit older to get his autograph at the time. But it was actually Adam West, no Robin... Just Adam West coming up with his Batmobile and he was giving the school a lecture on safety, you know. Then he went into Glasgow and did a few promos about safety and all that. The real Batman, Adam West, always remember the big Batmobile coming up the road.

Ref: Opening of Ruchazie Primary School, opened in 1958. Glasgow City Archives.

Ref: Ruchazie Primary School, opened in 1958. Glasgow City Archives.

In the 1970s Ruchazie faced a struggle to recruit teachers due to lack of suitable housing for them locally. It was reported that some teachers were even temporarily housed at Stirling University, 30 miles away, and travelled in every day to teach. Alongside housing, transport also proved difficult. Long-standing teacher Miss Young, who had been at the school since it opened, was forced to leave her job as the unreliable bus service eventually made her journey untenable.

By the 2000s, both Ruchazie Primary and St Philip’s had been merged with others as the population of the community fell. Ruchazie is now served by St Rose of Lima and Avenue End primary schools.

1960s And 1970s: The Community Matures

The early years of the scheme saw thousands of people removed from their previously tight-knit communities in different parts of Glasgow and thrown together in a new area. Ruchazie had become home to people from different backgrounds, including both Catholics and Protestants, but the community didn’t yet have its own churches. In 1954 a Church of Scotland minister was inducted and held services in Milncroft Hall, before the building of Ruchazie Parish church the following year.

Mary Sinclair-Ferguson’s mother was Catholic and her father Protestant, and she was raised Protestant. She remembers:

We had the church there, obviously we went to Brownies and Guides and my brother went to the BB’s [Boys’ Brigade] and stuff like that. We went to church quite a lot, my mum always made sure of that.

Although from a mixed family, Mary remembers some tension between Catholics and Protestants locally:

I loved Ruchazie Primary School, but I remember away back in the days when they used to fight with the Catholic school, St Phillip’s School, because it was like a border line between them.

Brian Tollett recalls the school reinforcing boundaries between the two communities:

Two schools used to come out at the same time, play time, right. They’d all go on the football pitches and play football. And then they got a new head teacher and a new priest and he didn’t like this. So, the Catholics got a different play time and a different dinner time, and they got a big fence put up to separate them. So, to me that was just pure sectarianism.

Christine Duke is Catholic and grew up in Ruchazie in the 80s. She recalls good relationships with friends of her age, but the mention of Orange walks hints at sectarian tensions never far away:

I was Catholic, I went to St Phillip’s, it was fine. I had a best friend who was Protestant who went to Ruchazie Primary, and it was never an issue. There was never any bigotry or ‘oh she’s Catholic and she’s Protestant’, we all mixed all the time, there was no fighting. So, my best friend Claire she would always come, she was at my Holy Communion, she was at my Confirmation. She was clueless, she didn’t have a clue about any of it, she would laugh most of the time. When it came to everybody crossing theirselves with the Holy Water, she actually washed her face with it, she didn’t know what she was supposed to do, but yeah there was never an issue. We would always… and I would used to go to the Orange Walks with Claire, so it was always a shared thing between the two of us.

Despite their differences, one thing the lack of amenities in Ruchazie did ensure was that the community had to work together in taking it upon themselves to organise their own clubs and activities for adults and children alike.

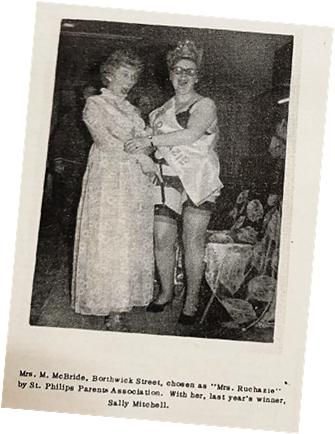

In 1962 the inaugural Ruchazie Civic Week, organised by locals, brought people together for fairs, entertainments and activities. As the community matured into the 1970s, proactive local residents set up their own groups, including a luncheon club, bowling club, karate and chess clubs, and even a boxing club set up by one-time Scottish champion John Convery, who lived locally.

A Tenants’ Association was established, which found its voice campaigning on local issues, including problems with the housing stock which was by now showing its age. Following a lengthy local campaign, in 1976 Ruchazie Community Council was formed, enabling residents to advocate for themselves, and giving them a platform to raise local issues and improve their community.

A grassroots newspaper, the Craigend and Ruchazie Review, was written and printed by local residents throughout the 1970s. It documents a time of great change in the area, when a community of those who had been the first to be born and brought up in Ruchazie were now raising their own families there.

Grace Wright worked at the Ruchazie Review in her twenties and remembers the paper being a helpful resource to keep the community updated with what was going on:

The Ruchazie Review it was called, I got involved with that. So, you had to find out who was getting married, birthdays, what was happening in the scheme, used to put recipes in, kiddies’ craft stuff, so just any news that was going about. Gerry Burn… he would do most of it, but just if there was anything that I had heard of, you know, you would write it down and hand it in. And then they would put in, like, the dances, you know - things that were going on in the scheme. Christmas events or whatever… It was quite good fun when that started, I quite enjoyed it. You would take photographs of the weddings and stuff like that or kiddies’ birthdays or parties, you know, just all the kind of usual stuff that’s in a local paper. And the shops would advertise and you would go round to make sure the shops wanted to continue to advertise… You had deadlines, you know, there was deadlines to have any news in, recipes and craft work, that all had to be in for a set time. Weddings and photographs had to be in for a set time for them to be able to get the photographs developed for the paper and things like that.

Ref: ‘Mrs M. McBride, Borthwick Street, chosen as ‘Mrs Ruchazie by St. Philips Parents Association. With her, last year’s winner, Sally Mitchell.’ Ruchazie Review, 1976.

Transport

The main transport artery in Ruchazie was, for centuries, the Monklands Canal. Opened in the 1770s to make it easier to transport coal from the collieries of the Monklands into the city of Glasgow, the canal brought barges back and forth along Ruchazie’s edge for two hundred years.

Although officially closed to navigation in 1952, people who moved to the new houses in the 1950s and 60s remember barges still occasionally plying the route to and from the city. As children whose gardens backed on to the canal, they recalled making rafts to play on the waters, and the wooden bridges that crossed from Ruchazie into Cranhill on the other side.

Ref: The Monklands Canal at the edge of Bankend Street, date unknown. The weeds growing in the canal show this was not the busy route it once had been.

Since the building of the new housing schemes, Glasgow had continued to pursue a development programme to modernise the city, which would see it bulldoze established neighbourhoods to make way for new transport links. Started in 1968, the inner-city section of the M8 motorway (originally called the Monkland Motorway) would fill in much of the old Monklands Canal and provide quick and easy transport links to and from the city - or so it was thought.

Anyone who has ever driven on the M8 at rush hour can’t help but raise a smile at the Ruchazie Review’s prediction in the 1970s that “Prospective neighbours can console themselves with the fact that present-day petrol prices and the drop in car ownership figures should ensure a relatively unused expanse of concrete”!

Ref: Bankend Street again, this time with construction underway on the second phase of the Monkland Motorway, which would fill in the canal and complete the route of the M8 past Ruchazie. The houses have since been knocked down and replaced with newer builds, though the Cranhill tower blocks on the right remain. Photo taken from the Scottish Roads Archive.

https://twitter.com/ScotRoadArchive/status/1539594056535199744?lang=en

The building of the motorway caused years of disruption for Ruchazie residents, with lorries and cars filling the scheme’s streets as traffic tried to find rat runs to avoid construction work. Things were particularly bad after the first phase of construction was completed in 1975 but before the second phase started in 1979. At this time, the new motorway ended at Cumbernauld Road, and motorists had little choice but to drive through Ruchazie to rejoin the Edinburgh Road on their way east.

Families were especially worried that the streets were becoming unsafe for children, particularly when young Ann-Marie Maina was knocked down on Gartloch Road, suffering a fractured skull and broken leg. Things got so bad that in summer 1975, local mothers came together to form a human barricade to block off traffic to Avenue End Road.

If car travel brought headaches to Ruchazie, buses proved equally fraught. As with other amenities, public transport links to the new housing schemes often felt like they’d been an afterthought.

Gerry Wallace moved to Ruchazie with his family in the 1950s. He recalls:

The only buses that came through Ruchazie, we knew them as the blue buses, which were Alexander, and there was one SMT bus about every three hours then. They didn’t have any Corporation buses, unusually, for all the east end of Glasgow housing schemes, Ruchazie was one of the few that didn’t have any Corporation bus service.

Despite Ruchazie’s proximity to Glasgow, locals lamented the poor bus service that left them cut off from the city and unable to travel easily for work, shopping and leisure. In the 1970s, the diversion of a key bus route from Ruchazie to Craigend had the Ruchazie Review jokingly advertising “Lost - several years ago, Bus Service 1B. Will those who removed it please return it to its rightful place at Ruchazie Terminus”, complaining “we have now become accustomed to standing at bus stops in wind, rain snow and sunshine watching buses run past us full.”

Mary Sinclair-Ferguson explains that poor transport links are a problem that still persists today:

They look off our wee 33 bus which is the bus that took you from Ruchazie to the Forge [shopping centre], and a lot of older people used that bus and now there’s no way for them to get there because you would have to take like a 38 bus which isn’t a very good bus either, you’d have to go from there to Riddrie and then get a number 8 which takes you away around Duke Street, the Gallowgate… It’s pretty bad for older people, especially older people, people with children, but the 33 bus took you right from your stop right to the Forge and brought you back. It wasn’t a very good service because it went off at 3 o’clock and then didn’t start until 9 in the morning, so people going to school and going to college and that would never be able to use that bus. The 38 bus is really bad and that’s the only bus we’ve got now and it’s not as frequent as it used to be.

Difficult Times

Ref: Frequently published advertisements for John’s van services, in the Ruchazie Review, 1970s

After the first optimistic years of the scheme, and despite the gradual coming together of the new community in Ruchazie, the area faced its share of challenges in the 1960s, 70s and 80s. This was a time when problems were emerging with the huge housing schemes that had been thrown up so quickly in the 50s and 60s, and Ruchazie was no stranger to the social issues and violence which received enormous media attention in neighbouring Easterhouse in particular.

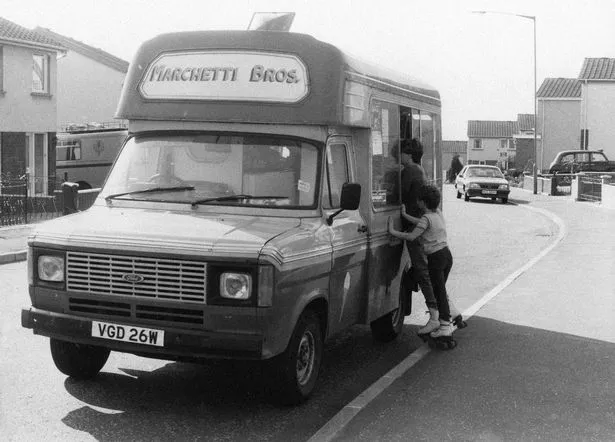

With few established amenities, in particular for young people, petty rivalries between neighbouring schemes could lead to anti-social behaviour and sometimes violence, as gangs protected their boundaries. While the new housing estates were home to thousands of people, a dearth of shops meant that mobile vans selling groceries, cigarettes and, in some cases, drugs and stolen goods, plied a busy trade around Ruchazie and neighbouring schemes.

Ref: Marchetti Bros. Ice Cream Van, 1980s.

With money to be made, those running the vans fought for territory, and violence and intimidation were almost daily occurrences. The skirmishes became known in the media as the “ice cream wars” given many of the mobile shops operated out of ice cream trucks.

Clashes came to a head in 1984 with a tragic incident involving the Doyle family from Ruchazie. 18-year-old Andrew Doyle, a driver for the Marchetti firm, had already been shot at through the windscreen of his van, in a move intended to intimidate him in retaliation for his refusal to distribute drugs on his run, and attempts by rival firms to take over his van’s route.

What is thought to have started out as a further intimidation tactic escalated with tragic consequences when, on the night of 16 April 1984, the front door of Doyle family home in Bankend Street was doused with petrol and set alight.

Members of the Doyle family, and three others who were staying in the flat that night, were asleep at the time. In the ensuing fire, five people were killed, with a sixth dying later in hospital. James Doyle (aged 53), his daughter Christina Halleron (25), her 18-month-old son Mark, and three Doyle brothers, James (23), Andrew (18), and Tony (14), all lost their lives.

This tragic event cast a shadow over Ruchazie for years to come and gave the area a reputation many locals felt was undeserved.

Christine Duke recalls:

There was an incident that happened, it was actually the year I was born, I can always remember it getting spoke about when I was growing up. But, it’s again, whenever you speak about Ruchazie, that’s the first thing people think about which then they just automatically think ‘aw gangs and drugs...’ but it’s not like that at all.

Christine remembers some skirmishes later into the 80s and 90s as she was growing up, particularly between those who lived in opposite ends of the scheme (the ‘Low End’ and ‘High End’), but not the same levels of violence as had been seen previously:

Obviously, you get your gang fighting, but it was kinda, ‘I’ll chase you and you chase me back’. It was Ruchazie Low End and Cranhill. I know that in the High End, I think they might have fought with Craigend, I think, or the Cobbie [the area around Cobington Place]. I don’t know what they done, but with the Low End it was Cranhill. But that’s what it seemed like, they were just kinda chasing each other.

Ruchazie Today and in the Future

The original development of Ruchazie had provided a new start for many families escaping the poor housing conditions of inner-city Glasgow in the 1950s and 60s. But ironically, the scheme itself was by the 1970s suffering the same issues of overcrowding, poor maintenance and unsafe conditions the families had fled just a few years before. By this stage, some residents were already moving away - even back to central Glasgow - while others pressed for redevelopment and improved living conditions.

Over the coming decades the population of Ruchazie would decline from a high point of around 10,000 in the 1970s to under 3,000 in 2008. Partly this can be explained by the redevelopment of housing stock which saw many of the original blocks of flats - so innovative in their design at the time - replaced with smaller single dwellings, as can be seen at Bankend Street.

Ref: Original Bankend Street flats (left) and replacement housing.

https://twitter.com/pmarsh226/status/1099416554847039490

In 1993, Ruchazie Housing Association was formed and began a programme of regeneration; this saw them acquire council housing stock that had been unimproved for decades and replace it with new housing. Over the next 20 years, they would replace dilapidated flat blocks with lower-occupancy units. The Housing Association now manage 225 properties in the area.

Ref: Claypotts being demolished, year unknown. Photo taken from:

https://www.flickriver.com/photos/12946121@N04/tags/ruchazie/

Speaking in 2015, Bill Nicol, director of Ruchazie Housing Association, said he believed that low-density housing directly contributed to lower levels of crime in the area:

The buildings are secure by design, you have less common areas, more defensible space, more ownership by individuals and less ‘no man’s land’ uncertain areas. [The new homes] are easier to manage and much easier to police.

After reducing the number of houses available in the area, and the improvements this has brought, some residents feel there is now the need to create more houses, building on the positive developments of recent years. Christine Duke explains:

Obviously people who have moved into the houses, they’ve started having families, their families are growing and there’s just not enough housing for them, to move into bigger houses… The turnover isn’t - it just isn’t good. But because of that they’ve not built any new more houses, we need more houses in the community. To keep them in the community because more people are moving away. Whereas years ago, people who stayed in the community, stayed in the community, they didn’t move away.

Alongside the redevelopment of housing, Ruchazie has also seen other recent changes that have brought a renewed sense of pride and ambition to the community.

Brian Tollett was an active volunteer in Ruchazie in the 2010s and started Ruchazie Poverty Action Group with other local residents to ensure people had access to reasonably priced food. With a lack of supermarkets locally, and smaller shops charging higher prices, the group sourced fresh fruit and veg and sold items in small, affordable quantities. He recalls:

We went to the market and we used to buy fruit and veg, I used to go down there at five o’clock in the morning and I knew all the guys from all the stands. And I used to go round and I used to haggle them and get a good price and all the rest of it. And I’d get the stuff and we’d bring it back up and we’d go to Ruchazie Parish Church, and we would set it all up there. And we would sell it at affordable prices so people could get fresh fruit and veg. And then we applied for funding from the Plunkett Trust and they gave us £5,000 worth of funding, it was for someone to come in and learn us about bookkeeping and all the rest of it and give us ideas.

“And then he come up with these ideas, he came in one day and says, ‘Oh yeah I’ve got a big pile of labels for you’ - Ruchazie Poverty Action Group. Ruchazie Poverty Action Group lentils, broth mix, marrowfat peas…, Ruchazie garlic and all that. And we had them all bagged and everything and we were putting them out, and we were hearing people, ‘Oh lentils I’ll buy a packet of lentils.’ We used to sell hundreds and hundreds of them, even tea bags, coffee, wee tubs of sugar, like ground sugar, salt, pepper, oh, we done a lot.

Ref: Ruchazie Poverty Action Group. Image taken from Evening Times.

https://www.glasgowtimes.co.uk/news/14764009.ruchazie-community-group-feed-locals-and-tackle-food-poverty/

Founded a few years later, in 2020, Ruchazie Development Trust, known as Growing21, has promoted a number of projects to engage with the community and regenerate and enhance Ruchazie.

One such project is Ruchazie Pantry, which opened in September 2020 and built on the work of Brian Tollett and others and their efforts to bring affordable food to Ruchazie. Taking the model developed successfully elsewhere by the charity Fareshare, the pantry receives donations of food from supermarkets and retailers and sells them on to the community at affordable prices. Rather than operating on a food bank model, it means residents pay a membership fee, then pay a flat rate to choose the items they want to buy each time they visit.

As well as making food more affordable - in a community that is still among the most deprived in Scotland - the Pantry means people in Ruchazie don’t have to travel as far, or take a bus, to get their food shopping. Tina Blakely remembers the early days:

Going back to when The Pantry first opened in August 2020, it very quickly became winter, it was dark, it was cold. I remember one night being out there, dancing with a tub of sweets because it was freezing. We were in Covid, everybody was miserable, and there was these two old ladies who had been seen coming probably from the August, and I’d said, “Why do you always come on a Monday night? Why do you not come on a Tuesday morning when it’s quieter and you’re not waiting in a queue?” And they said, “Because (so and so) comes on a Monday night and I’ve not seen her for years”. And they only live a street away but they didn’t mix because of what I said about Easterhouse about the divide. Ruchazie is very much divided so now they both volunteer here on the same day! It’s crazy, so lots of amazing stuff happened through The Pantry.

Alongside affordable food, the Pantry team also organises activities for the community, including cooking lessons, art sessions and family activities, and offers volunteering opportunities. They are currently working on plans to expand into a neighbouring unit, which would allow them to open a cafe and provide further space for community activities.

Ref: Ruchazie Pantry, 2020.

Alongside the Pantry, plans are also under way to redevelop the site of the old Ruchazie and St Philip’s Primary Schools, which has lain derelict since the early 2000s. Under the proposal, allotments and a community growing space will be developed, which resident Christine Duke feels will play an important role in bringing the community together further:

We are going to have the allotments as well, which is, I’m very excited about personally, cause I feel that it’s just going to be a gathering place for the community. And it’s going to bring the Low End and the High End together, because for many years it’s always been the High End and the Low End. We’ve never actually been as one. Whereas hopefully now with these changes coming we are going to be the one big Ruchazie and we are going to get rid of the High End and the Low End.

Brian Tollett agreed:

Now there’s none of that in Ruchazie, there’s no High End or Low End or none of that, it’s just Ruchazie. People are saying now ‘Ruchazie’, know what I mean. It’s just Ruchazie.

The community of Ruchazie, created just 70 years ago, is continuing to settle, adapt, and grow from strength to strength. Reflecting on the history of the place she has called home for 40 years, Christine feels optimism for the future, and the opportunities for residents and families:

It’s not just going to be the allotments, we’re going to have like sports places, playspaces, just spaces for everything and anything that everybody wants to do. There’s always going to be something there for whoever is there, it’s going to be great, it’s going to be brilliant to see and witness.